Women in Badakhshan React to New Restrictions

Women and girls in Faizabad, the capital of Afghanistan’s northeastern Badakhshan province lament the latest Taliban restrictions forcing them to wear a burqa or niqab when they are out.

Written by Shabana Farahmand

FAIZABAD, BADAKHSHAN — “Let me go and get a niqab, you will see me with one next time!”

“Promise?”

“Promise!”

This rather peaceful exchange took place between a woman wearing a green scarf paired with a mask, and a man wearing a black turban and white coat, the uniform for the Taliban’s religious police.

Although she is technically covered from head to toe, her outfit still does not conform with the new standards the Taliban has set for women in public spaces.

The man is an officer of the Taliban’s Directorate of Vice and Virtue, the group’s religious police in northeastern Afghanistan’s Badakhshan province.

Nearly two months have passed since the Taliban's religious police took strict measures on how women dress in Badakhshan, specifically in its capital of Faizabad.

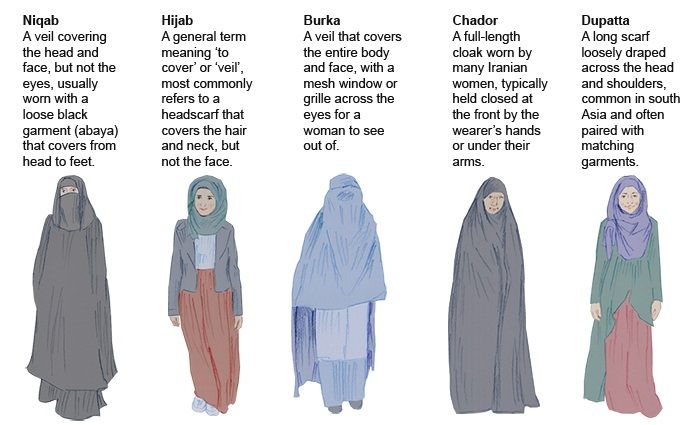

According to the Directorate of Vice and Virtue, proper attire for women in public is either a burqa or niqab. Women and girls wearing other forms of hijab are stopped by the religious police stationed at mobile checkpoints throughout the provincial capital, and asked to explain why they are not wearing proper hijab. They are then ordered to go back home and only return after changing into the proper covering.

Many women Alive in Afghanistan interviewed decried the Taliban’s move to further restrict women, saying the religious police insult, belittle, and harass women and girls across the city.

“I know what to wear and the value of the hijab. All women and girls in Badakhshan observe hijab,” Mursal, a student at the Badakhshan university, told Alive in Afghanistan, clearly angry. Mursal said she has witnessed girls being turned away from university gates for not wearing the group’s defined dress code.

Mursal said officers of the Taliban’s religious police chase after cars if they see a girl riding inside who wears something they do not approve of.

“We were stopped on the way to university today and they even checked our fingernails. They wanted to slap a student for wearing nail polish, but the girl ran away. They called ahead to the next checkpoint to apprehend and punish her,” Samia, another Faizabad resident, said.

Samia believes women in her city already have a strong understanding of the value of hijab and asked the Directorate to stop disrespecting women by publicly confronting them in such a manner.

La’al Mah, a university graduate said, “The Directorate has taken strict measures against women on the issue of hijab. They don’t care if the woman has economic or respiratory problems. The behavior is against Islam.”

Islam provides accommodations for women with reasonable health issues when observing religious practices like fasting and the Quran itself does not mandate any kind of hijab to be worn in public. The economic crisis has exacerbated the challenges that women already had affording new clothes and some may not have the resources to purchase clothing that fits the Taliban’s restrictions.

Yalda, a high school student who has not been to school for over a year said her family forced her to wear a burqa after the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August of 2021 to limit harassment by the group.

“I hate wearing a burqa and I feel like a prisoner. That’s why I don’t leave the house often, so I won’t be forced to wear it,” Yalda told Alive in Afghanistan.

According to Yalda she was able to wear the clothes of her choice before the Taliban took over but that she no longer has a choice in the matter.

The Taliban government’s interpretation of Islamic Sharia law is seriously problematic, according to the women who spoke to Alive in Afghanistan.

Psychological safety has disappeared for women in Badakhshan. Women and girls who are breadwinners for their families can hardly leave their homes for fear of being confronted by officers of the Taliban’s religious police.

“Instead of focusing on women’s hijab, open girls schools for us,” Yalda said, exasperated, “What a bitter and sad life we Afghans girls have.”