Villager Establishes His Own School

Abdul Qader saw no educational facilities upon return to his hometown of Qader Khan, a village in Afghanistan’s Helmand province. So he took it upon himself to open one.

— One Day in Afghanistan—

Written by Nematullah Hemat

NAHR-E SARAJ, HELMAND — For many children in large parts of Helmand, access to education is a dream that remains unfulfilled. That is because Helmand is one of the most volatile provinces in southern Afghanistan and it’s residents have faced near continuous war over the past two decades.

According to a press release by the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in April 2022, Afghanistan has one of the lowest literacy rates in the world. Information on provincial literacy rates has not been collected.

“Afghanistan’s illiterate population (aged 15 and above) has been estimated at 12 million (7.2 million female, 4.8 million male) from a total population of 39.6 million[,]” the release said.

But some Afghans have taken the initiative to educate children in places where schools did not exist before. In today’s One Day in Afghanistan episode, Nematullah Hemat visits a school in Nahr-e Saraj district that was opened by Abdul Qader Pasoon in his hometown, to educate 200 children, including 70 girls.

I leave Lashkargah, the capital of Helmand for Nahr-e Saraj at 6:18 in the morning and arrive at the Qader Khan village after 2 hours and 33 minutes. Qader Khan, located on the southern banks of the Helmand River, has plenty of water to irrigate the surrounding farmlands. Villagers can be seen farming on their land all across the village. A number of children are grazing their animals near a canal that brings water from the Helmand River.

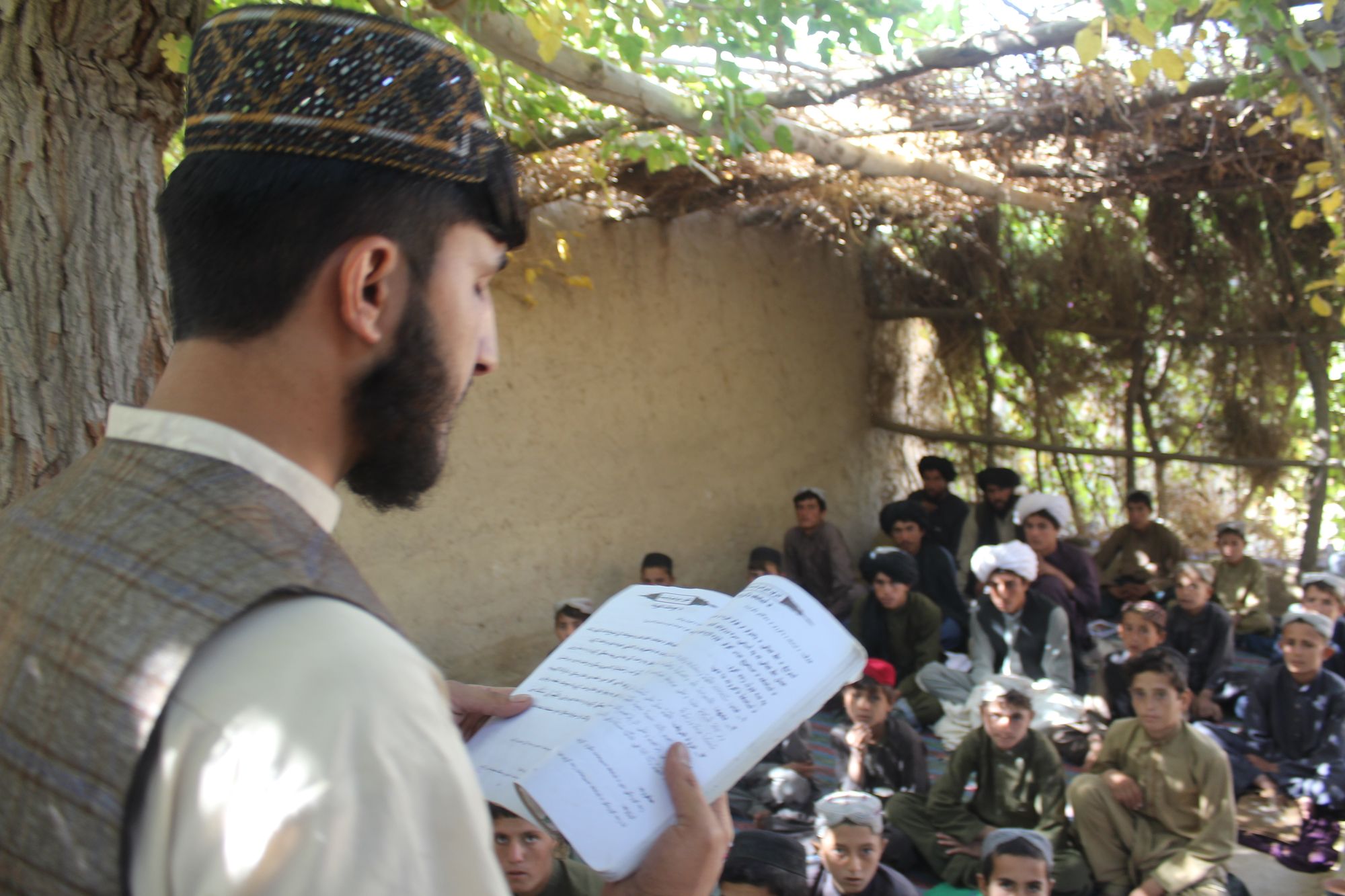

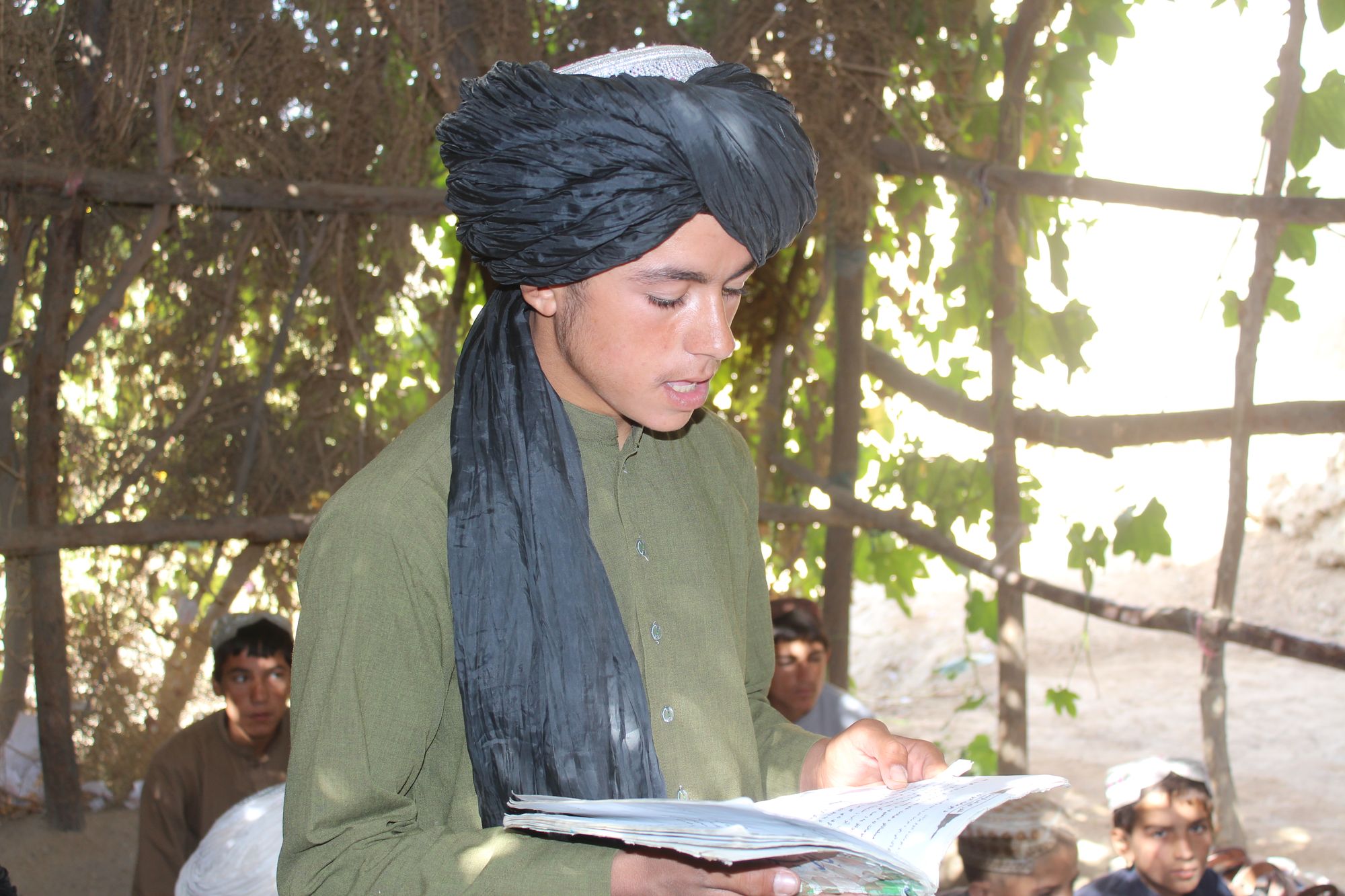

As I get closer to the school, the sounds of children repeating their lessons reaches my ear after traveling down the street. As I get closer to the school, located inside a mudhouse, the first thing I notice is the children garbed in colorful traditional clothes passionately repeating their lessons along with Mr. Pasoon.

Abdul Qader walks over and welcomes me before I reach the classroom. He is holding a pashto book with a colorful plastic cover to avoid damaging the book.

“Zhwand! Zhwand!” The students chant as Qader and I enter the classroom. Zhwand is used as a greeting in Pashto and means “Live long.” Students sit on plastic mats with their books and notebooks resting on top of their bags in front of them.

Qader calls on Osman, his brother, to prepare some tea and take me to their guesthouse. The house looks very old–according to Qader it was built by his grandfather some 88 years ago.

Osman brings us tea with fresh bread some minutes after we enter the guesthouse. Meanwhile I notice something strange and out of place. There is a big TV with a wooden frame sitting on a shelf that looks like it has not been turned on or used for months.

“A TV in here?” I think to myself.

Qader notices my astonished look, “When villagers saw us watching TV, they asked my father at the mosque to stop watching it. Residents decide the issues here, and we have no option but to obey.”

Afghanistan is a very traditional country and Afghans, especially those living in the countryside, tend to be religiously conservative. The villagers in Qader Khan believe it is a form of infidelity to see people on TV who are not clothed according to local customs. Therefore, they believe TVs shouldn’t be allowed because it may cause families to deviate from religious edicts.

After finishing breakfast, we head back to the classroom. Although boys and girls both attend the school, they are segregated.

“We study here but without any books, notebooks or pens,” 12 year-old Fatima, the oldest female student, says. Her black eyes distinguish her from her other classmates. Children and their parents are asked to bring their own books and stationery supplies to school. The facility doesn’t provide any.

Shaqiba, another student who looks very happy says, “I am learning writing and how to pray.”

Robina says they have learned about the rights of parents, in addition to writing and prayers. Robina wants to become a doctor when she grows up so she can help her people.

Nasibullah, another student, is happy to have the chance to learn how to recite his prayers, but at the same time he is sad because he does not have any books, nor a notebook to write down the prayers.

Standing in the courtyard of the school he started, Abdul Qader tells Alive in Afghanistan, “I moved back to the village after years and noticed all children, youth and residents without any type of education. Seeing that drove me to do something and help educate the people of my village.”

The next closest school to the Qader Khan village is about 20 kilometers away. Even in the district center there are a limited number of schools, and these are exclusively for boys. The district center itself is 85 kilometers away from Qader Khan.

When Qader returned to his hometown around 14 months ago, following the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August of 2021, he wanted to open an educational facility. Unfortunately, as he says, “Initially the parents denied sending their kids to study.”

Qader had to go to every parent’s home and convince each one to send their children to his facility, “Now they are all willing, and are even cooperating with me.”

According to Qader, more than 2,000 children live in the area that need schooling, but he can only accommodate 200. Qader and Mawlawi Matiullah, the Mullah for the village, are the only ones teaching at the school.

Qader himself only studied until 10th grade. He and his family left their village for Kandahar City, in the neighboring province, around 11 years ago due to the ongoing conflict that displaced thousands of Afghans.

Although he couldn’t continue his school in Kandahar, Qader was able to take short term religious, journalism and calligraphy courses.

“I don’t want the current generation to experience what the previous generations did, being deprived of education. So I try to teach them what I have learned,” Qader says.

Qader urges the government to pay attention to remote areas where he says many children are being raised illiterate.

“Education is every human’s right, and the government must focus on all of Afghanistan equally,” Qader says.

Mr. Pasoon’s facility teaches religion, social studies and language in three shifts, 5 to 7 am, 8 to 10 am and 1 to 3 pm.

The second shift of this morning’s classes is dismissed at 10 am and I head to the village mosque to talk to Mawlawi Matiullah.

Matiullah says, “I have faith in modern studies and am happy that the children are able to learn both religious and modern subjects after Abdul Qader’s return.”

In addition to Mawlawi Matiullah, Abdul Qader’s dad, Abdul Qudoos also praises his son’s efforts, “I am really happy with the step my son took. Although he is not well-educated, he knows how to interact with the village elders very well.”

Qudoos believes children must all study, whether it’s modern or religious studies.

It's now noon and time for lunch. Mr. Pasoon has another guest in addition to me so we head towards his guesthouse. His family has prepared lamb Shorba, a traditional soup eaten with bread.

As we are eating, 14 year-old Mohammad Omar, a resident of Qader Khan, enters the guesthouse and without any introduction, says, “I want to enroll myself and study.”The boy is told that he can come to the school but must bring his own notebook and pen.

Mawlawi Mohammad Ewaz Ansari, the head of Helmand’s Education Directorate has also expressed concern about the lack of schools and educational facilities in his province saying, “Children in most of Helmand have been deprived of education. Although they understand the value of education, the platform has not been provided for them.”

After lunch I am walking along the banks of the river when I meet a 72 year-old man who introduces himself as Haji Abdul Rashid. Rashid says he is illiterate but appreciates Mr. Pasoon’s initiative.

“It’s a big step towards the development of our society,” Abdul Rashid tells Alive in Afghanistan.

I start walking back to the school around 1 pm. Girls and boys are going to the school in small groups. Upon getting closer to the school, the melodic sounds made by the children’s voices momentarily take me back to my childhood.

In the school, the children have lined their shoes in organized piles, are sitting in rows, and repeating what they have learned while moving their upper body back and forth. Their books and notebooks are kept on top of their handmade bags in front of them.

After greeting them, I ask the children some questions about religion and am amazed by their prompt responses.

After a short break, Mr. Pasoon starts teaching. Today he teaches four subjects; including prayer instructions, calligraphy, social studies and Pashto. This class lasts until 3 in the afternoon. While children are studying, my eyes roam the village outside the house and I notice two children loading a bail of hay onto mules. Then they follow the mules barefoot after loading them.

I keep thinking that those children need access to education as well and wish they had the opportunity to study.

At 4 pm I have to say goodbye to Abdul Qader and head to Lashkargah, ending my day with him. For more information about the situation of children and education, please read Alive in Afghanistan’s articles on Education and Children.