The Children Who Have Never Set Foot in School

The ugliest toll of war in Afghanistan, has been depriving children of their right to education. In this One Day in Afghanistan episode, we focus on children in Helmand’s Marjah district, who have never set foot in a school.

— One Day in Afghanistan —

Reporting by Nematullah Hemat, written by Abdul Ahad Poya, edited by Mohammad J. Alizada, Brian J. Conley, and Michelle Tolson

Alive-in is a not-for-profit media agency that mentors journalists from underrepresented communities to increase local and international understanding. Subscribe to receive our stories directly in your inbox.

If you are able to support our work financially, please click the button below.

MARJAH, HELMAND — Many children in different parts of Helmand Province in southern Afghanistan don’t know how to read and have never gone to school. Access to education for children in large parts of Helmand, one of the largest provinces in Afghanistan, has been non-existent. This has been due to the continuous war in the province over the past two decades.

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) report in March of 2020, although the literacy rate increased from 34.8 percent in 2017 to 43 percent in 2020, over 10 million youth and adults in Afghanistan remain illiterate.

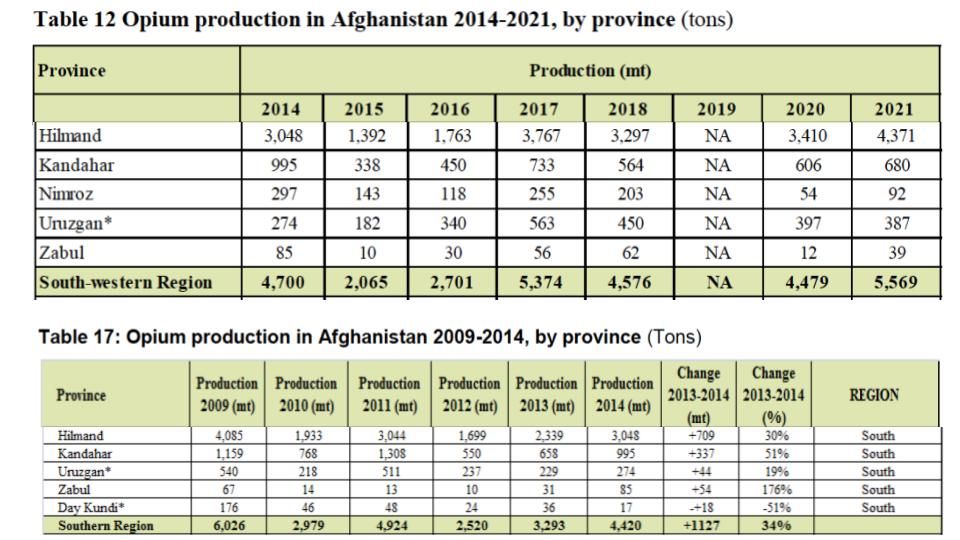

The near constant attacks against international forces and Afghanistan’s previous government over the past 20 years, left little time for educational institutions to develop in formerly restive districts, such as Helmand’s Marjah district. Instead, the cultivation and sale of opium, the main source of income for the Taliban, flourished significantly. According to data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Helmand has been the largest producer of opium over the past decade. For more information, read UNODC’s annual Afghanistan Opium Survey 2021 here and 2014 here.

Marjah has not only been a hotbed of insurgency against the Afghan government and its foreign allies since Taliban were overthrown in late 2001, it was also nicknamed “kushtargah - slaughterhouse” by journalists and the general Afghan public. Due to the perceived risk, no one dared to visit this district over much of the past two decades. And for good reason, as civilians who didn’t support any side in the war could easily fall victim to crossfire, roadside bombs, night raids, and airstrikes. But after the fall of the previous government in August 2021, some of the most insecure areas in Afghanistan have become accessible to the general public to visit.

In today’s One Day in Afghanistan episode, Alive in Afghanistan’s Nematullah Hemmat visits Marjah’s Bismillah village in the Terkha Nawur area to speak to its children and their parents about their thoughts on education, or the lack thereof.

The day starts at 7:00 am, as I leave Lashkargah, the capital of Helmand, for Marjah. The roads leading to Marjah have been asphalted but are not in good condition. Explosives and munitions used in the years of war by all parties laid waste to bridges and the road, making it difficult to travel. After an hour and a half, I arrive in Bismillah village

As there are no schools or madrassas here, instead most children help their families harvest and transport wheat in 40° Celsius heat (104° Fahrenheit), while sweat pours down their heads and faces. Everyone stares at me and my camera with amazement and shock, like they have never seen a journalist with his work equipment up close.

As I have come here without any prior coordination, their shock is expected. It is now 9:00 am and I want to interview a number of children, but no one dares to speak with a stranger, let alone step in front of the camera while doing it. The children shy away and one tries to hide behind another’s back as I approach them. One of the children points to a boy cutting wheat alongside his older brother, saying, "Saifur Rahman can talk. Ask him."

The child, 12 year-old Saifur Rahman, puts away his scythe after hearing me call him and starts walking my way. There is no advanced machinery for cultivation here.

The shyness of the children doesn’t last long once Saif comes towards us. Wearing flip-flops and colorful southern-style hats, children now surround us, talking in a swarm like bees to the point of interrupting the conversation between Saif and I. Finally, I ask an elderly man from the village to calm the children down so we can hear each other talk.

"We want a school to be built here. We could farm and go to school if there was one,” Saif says. According to Saifur Rahman, the lack of schools are causing children to lose the opportunity to get an education with each passing day. Saif goes back to work after speaking to me.

Next, Hematullah, a 15 year-old teen harvesting wheat on his farm near Saif joins us after seeing me and the children buzzing around. Hemat, who uses social media, has access to a different world than the one he lives in. He expresses a passion for education that has yet to come true.

“There is neither a school, nor a madrassa here. My generation grew up illiterate, but I want to study and I do not want children younger than me to grow up illiterate just like us,” Hemat tells Alive in Afghanistan. Hemat’s favorite pastime is cricket and his favorite player is the renowned Afghan all rounder, Rashid Khan, but most people here do not own a TV, or have access to a suitable field where they could spend their time off playing cricket.

But the children here make do with what they can. They play cricket on harvested farms using homemade bats, and wickets. The rest of the time, they swim in water extracted from wells dug in the area that flow into large canals that irrigate the farmlands. The swimming is less for entertainment and more to escape the Helmand heat, and cool down after work.

According to the farmers, the wells are dug at least 60 meters deep to reach underground channels of water. One well can irrigate about 12,000 hectares of land for a year, then the farmers have to dig another well, about 20 to 30 meters from the old one.

It’s now 11:25 am and a number of children have stopped working and are swimming around in the water flowing through a canal, playing and throwing water on each other’s faces.

Spring and summer days are hot in Helmand and I’m sweating as I look around to find more children or people to interview. Two young, school age girls are gathering piles of harvested wheat and carrying them to a single spot. They are dressed in traditional, colorful clothes. Children around me say the name of the older girl is Subhana. But Subhana flees the area as I try speaking with her about today’s topic.

Girls in the village and region are only allowed to roam and work outside until they are 12, after that they are not to leave the house unless necessary.

According to the villagers that Alive in Afghanistan spoke to, there are no schools for girls in the entire district, and schools for boys are very few, with most of these located in the district center and along the main road.

It’s now 12:15 pm as I approach a man with a bushy beard who has tied a patu around his waist, carrying a shovel on his shoulder. He is heading home for lunch from his farm. His name is Torjan and the old man has been a farmer all his life.

“I have three children and am the guardian for four of my brother’s children. All of them are illiterate,” Torjan says. Torjan’s brother died after being caught in the crossfire during a firefight between the Taliban and Afghan security forces four years ago.

Torjan wants the Taliban to pay more attention to building schools and educating the children. He urges the Taliban and aid agencies working in the education sector to take action. And he is not the only one. Like Torjan, many parents in this area cannot send their children to school and do not have the means to build or fund a school.

For instance, Azad Khan is the father of six children who has come to the village for work. “I have three daughters and three sons. I will send them to a school as soon as one is built.”

Although religious studies are being taught at mosques, it is unclear whether the Mullahs themselves are sufficiently educated to teach the children what they need to learn. “I sent my son to a mosque for two years for religious studies, he didn’t learn how to even pray in that timeframe,” an elderly man who spoke to Alive in Afghanistan on the condition of anonymity, said “When there is no proper school or madrasa, this kind of education can never be effective.”

It is now 1:00 p.m. and the children, along with their older brothers and fathers, have stopped work one after the other and headed home. I head to the only shop in the village, which is next to the mosque, for lunch and prayers. The mulberry trees surrounding the shop have grown into a canopy to sit under in the scorching heat of Helmand. My lunch is a bottle of water and a pack of biscuits I bought from the shop.

After finishing my lunch, I enter the mosque to pray. Some elderly men have also come to pray but other than them, the mosque is empty. After finishing prayers, I ask the village Mullah about his opinion on education.

"There are not and have never been any schools in this area. The situation wouldn’t be as concerning if there were schools,” Mullah Jallat says.

The village Mullah calls on the Taliban and partner aid organizations to pay attention to children’s education and pave the way for them to acquire knowledge. According to Mullah Jallat, the villagers are far from being able to afford to send their children to study elsewhere.

I once again head to the farmlands so I can speak to more children, but the farmlands look like a ghost-town–everyone has gone home due to the sweltering heat. There are only a few children swimming in the stream but they shy away from talking to me.

I wait until 2:30 pm for the villagers and children to return, but no one comes out of their house. Helmand is normally quiet in summer afternoons as people escape the heat. They only come out later in the afternoon, around 4 pm.

Using this opportunity, I contact the Taliban’s head of the Directorate of Education, Mawlawi Mohammad Ewaz Ansari, who confirms that a large number of children across Helmand are deprived of education due to the long years of war.

“We are trying to speak with organizations working in the education sector to build schools across Helmand. Meanwhile, we have put in a request to the Ministry of Education for hiring teachers,” Mawlawi Ansari says. According to the directorate's information, there are a total of 430 public and private schools for a population of 1.4 million, of which 130 are girls schools.

Elders in the area tell me that over the past 20 years, there has been neither peace nor security for even three consecutive months, barring the opportunity for any school to be built in such a conflicted region.

Marjah is not the only district in Helmand that lacks access to education. Across Helmand, there are many districts where children have not had access to education due to the continuous war.

At 3:15 pm, after talking to the villagers and seeing no one else was ready to come out of their house, I decided to head back to Lashkargah. Because of the story of children, I cannot keep my thoughts away from their lives and ambiguous future.