The Apple Farmer Serving Travelers

Mahram Ali’s farmstand is the last stop before reaching a popular park along a highway connecting two of Afghanistan’s western provinces, Herat and Badghis, make it popular for tourists and locals alike.

— One Day in Afghanistan —

Written by Abdul Karim Azim and Mohammad J. Alizada

TAGAB LAJAM, HERAT — Agriculture is the main source of revenue for much of rural Afghanistan, a region that accounts for 74 percent of the country’s total population, according to a World Bank data chart.

In today’s episode of One Day in Afghanistan, Abdul Karim Azim documents one day in the life of 47 year-old Mahram Ali, a farmer who sells his produce at a roadside farmstand in Tagab Lajam, a village in Karukh district of western Afghanistan’s Herat province.

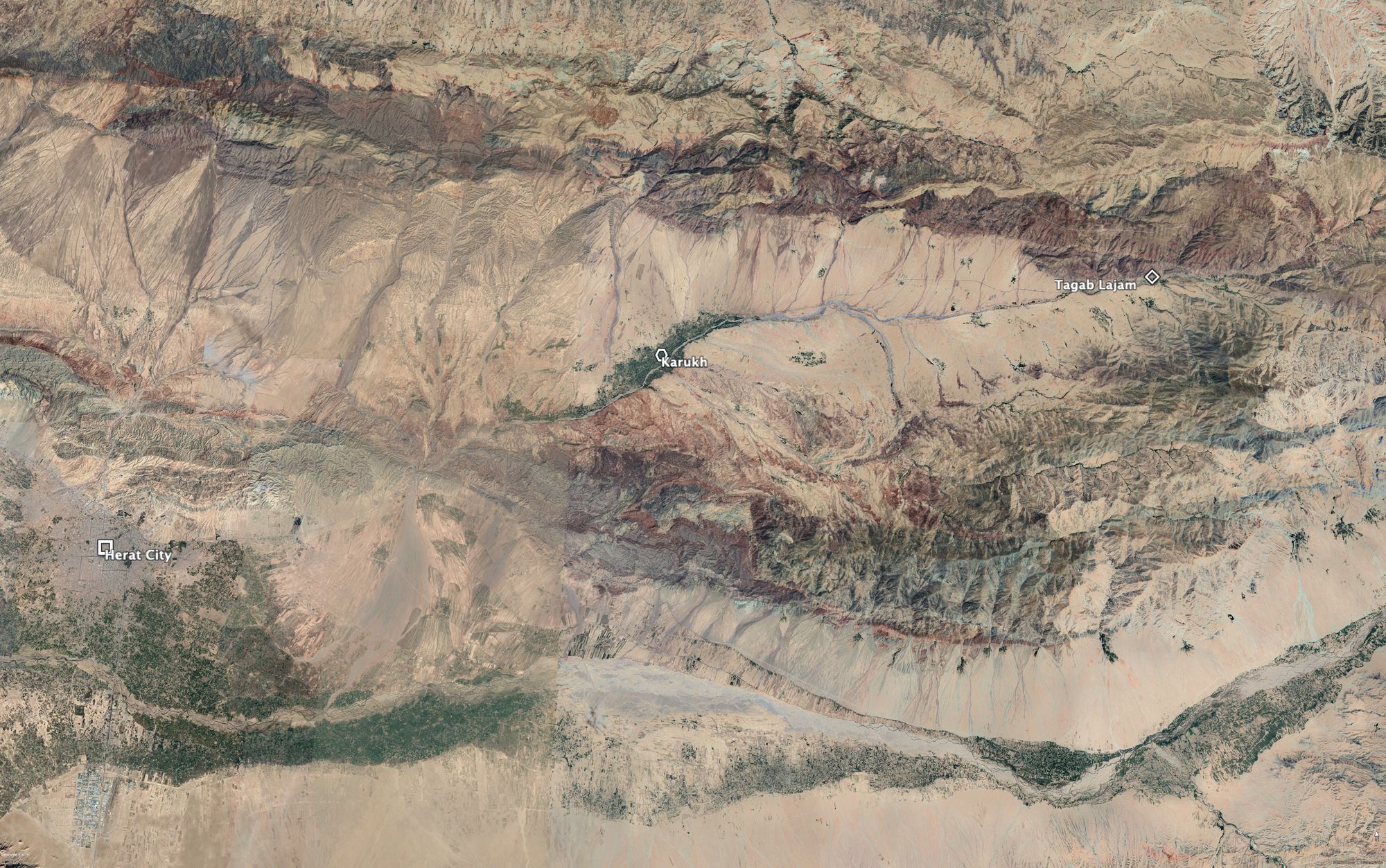

Tagab Lajam is located on the Herat-Badghis (neighboring province) highway, 38 kilometers northeast of Karukh and nearly 80 kilometers northeast of the province’s capital Herat City. At 8:30 in the morning, I hop aboard the only van going to Tagab Lajam from Herat. A single van carries passengers to and from Tagab Lajam daily, leaving Herat in the morning and returning in the afternoon.

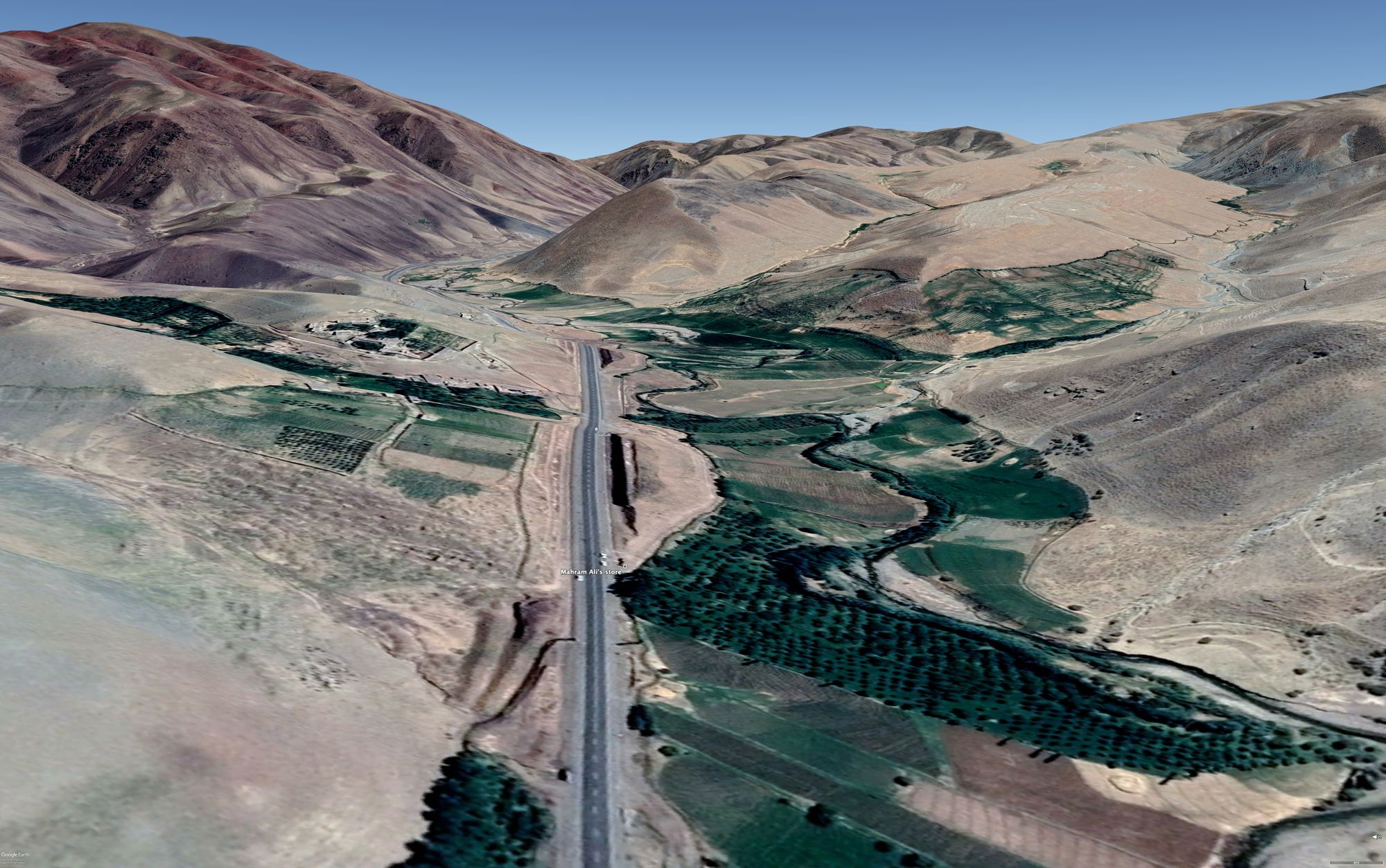

The road to Tagab Lajam is asphalt. The elevation increases as we leave Karukh district center behind. The land here is vast and feels empty, villages with patches of green farmland and small clusters of mud hut homes are few and far between. With just 10 kilometers to go, the beautifully colored maroon and olive mountain range, in the distance just minutes ago, now dominates the horizon to my left.

A small river to my right snakes its way from the valley to Karukh and Herat, appearing and disappearing behind bends in the road. It makes another appearance and with it, the farmlands dotting its banks. Tagab Lajam is not far, the driver says.

It’s 10 am when the van stops at Mahram Ali’s roadside stall on the right of the highway. Having arrived at my destination, I disembark. Mahram Ali wears a blue shalwar kameez and a gray vest. On his head he wears a black and white baseball cap that shades his face from the sun. As I approach he is busy selling apples to a customer.

Gazing at my surroundings, I walk along the gravel shoulder toward Mahram’s farm stand. I take a seat on an empty corner of the mud stall he built to display his produce. I study the kind way he interacts with his customer. The shop is a simple mud building with an open front, built on the side of a small hill. More than 10 cardboard and plastic cartons perch on the stand, full of red and green apples.

“You want some tea?” Mahram asks me once his customer leaves.

“I wouldn’t mind a glass!” I respond with gratitude.

Mahram pours black tea into my glass, which I sip while setting up my camera.

Mahram is the head of a family of nine, including his wife, six children, three of whom are girls, and his mother-in-law. Seven years ago he allocated half (4.04 hectares) of the land he originally leased from his late father-in-law to an orchard. According to Mahram Ali, the other half is used to grow vegetables.

“I grow apricots, peaches, plums, cherries, bahari (spring), and tirmahi (fall) apples and tomatoes. It’s now the season for apples,” Mahram tells Alive in Afghanistan. The apple trees are harvested in two seasons, spring and fall.

According to Mahram Ali, the hard work of farming begins in March. “At first we dig around the base of the trees, mix the black and white fertilizer and pour a full glass into the base of each tree. After that, we cut the dead or damaged limbs then we water the trees. Once the trees blossom, usually after two weeks, the first round of pesticides are sprayed. The second round of pesticides are sprayed and the trees are watered again when the apples are the size of walnuts,” Mahram Ali says.

Mahram says that he starts selling the fruit once they start to ripen. According to him, apricots are first to ripen, followed by peaches, and spring apples. Fall apples usually start to ripen in July and August.

“I first pay back any loans taken for farm expenses, then use the rest of the money to cover our daily expenses,” Mahram Ali says, adding that, “Thanks be to God the harvest from our orchard is enough to cover our household and medical expenses.”

He adds that sales are usually lower on weekdays, but get a boost during the weekend, usually Thursdays and Fridays in Afghanistan, “When people come here to take a break.”

Mahram Ali’s shop is the last stop before Band-e Sabzak, a park about 25 kilometers northeast of Tagab Lajam, that spans between Herat and its neighboring province Badghis. The park’s lush greenery attracts people from both provinces to visit on the weekends.

“I get to sell between 5,000 to 6,000 Afghanis on Fridays ($56 to $67 at current exchange rates),” Mahram says.

It's 11 am now. Customers come and go as we speak, buying what they want.

“Most of my customers are from Badghis and Herat who come here for sightseeing. It is better for me if my products are sold here as I do not have to wander much. If it’s not sold here, I would have to pay 50 Afghanis ($0.56) per carton to take my products to the market and sell them there,” Mahram says.

Mahram sells each kilo of grade A apples for 50 Afghanis and second and third grades for 40 and 30 Afghanis respectively ($0.56, $0.45 and $0.34). In Herat City, that same kilo of first grade apples are sold for 80 to 100 Afghanis ($0.90 to $1.12).

My phone shows that its 11:30 in the morning while Mahram laments the lack of a solid market, wishing the government would provide export platforms for domestic products, ban import of products from Iran or at least increase the customs’ tax on fruits imported from the neighboring country, “So that domestic products are sold at a better price.”

“We could store our products in cold storage if they were available and sell them when market prices are good, so we profit rather than lose money,” Mahram says while polishing the apples with a towel to make them shine for potential customers. Mahram wants Tagab Lajam to be registered with the provincial agricultural department so that the agency would pay attention to and provide agricultural equipment for the village farmers.

As the number of customers dwindles at noon, Mahram takes the opportunity to collect some more apples and water the orchard. Mahram’s orchard is conveniently located right behind his storefront. Part of the orchard is on a slope that runs along the river below. A channel of water that joins the river upstream about a kilometer eastward creates a natural border between the barren land behind the store and the orchard on its southern side.

I follow him into the orchard’s delightful atmosphere full of fresh air and away from the city’s pollution. Carton in hand, he approaches an apple tree, plucking the fruit one by one and placing them in the carton.

The cartons he is filling with apples are taken to the Karukh cattle market, open each Monday and Thursday of the week. The dual day bazaar also serves as a farmers’ market for villagers to visit and buy their groceries from.

Alive-in is a not-for-profit media agency that mentors journalists from underrepresented communities to increase local and national understanding.

If you are able to support our work financially, please click the button below.