Seasoned Teacher Opens School for Taliban’s Children

Former Afghan teacher opens a school in his village to educate children. The village lacked access to education for years due to the continuous war in Afghanistan.

— One Day in Afghanistan —

Reporting by Baryalai Ansari, written by Abdul Ahad Poya, edited by Mohammad J. Alizada & Brian J. Conley

Alive-in is a not-for-profit media agency that mentors journalists from underrepresented communities to increase local and international understanding. Subscribe to receive our stories directly in your inbox.

BALUCHI, ORUZGAN–According to a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) report in March of 2020, although the literacy rate increased from 34.8 percent in 2017 to 43 percent in 2020, over 10 million youth and adults in Afghanistan remain illiterate.

“Despite these achievements, however, there are still massive challenges and a great number of people who lack literacy and opportunities for continuing education in our country,” Mohammad Yasin Samim, a former Education Advisor, said in the report.

In today’s One Day in Afghanistan episode, our correspondent Baryalai Ansari profiles 70 year-old retired teacher Ghawsuddin Jalalzai. Mr. Jalalzai opened a school in the Baluchi area, about 25 kilometers north of Tarin Kot, the capital of Afghanistan’s Oruzgan province, where he and a number of volunteer teachers teach 270 students, including 77 girls.

After the Taliban defeated the previous government, Ghawsuddin knew educational opportunities would soon be tightly controlled. He decided there was an opportunity to help the children of his hometown at least learn to read and write. Ghawsuddin estimates as much as 95 percent of the area's population are illiterate. He is one of the rare residents of the Baluchi area that was lucky to go to school in the capital Kabul and has been a teacher in several Afghan provinces. For the past 10 years of his career, he was a teacher in Tarin Kot.

It’s 7 am as we leave Tarin Kot for the Baluchi area, nestled in a valley between high mountains that loom over a wide river . According to residents, Baluchi is home to around 500 families that number around 3,000 residents in total While looking for a school founded by Ghawsuddin people keep staring as though seeing a person wearing a baseball cap and carrying video equipment is out of the ordinary.

Mr. Jalalzai has sent one of his students to guide us to the school from the road. After walking among fields and farms, we reach the Mohammadia School at 8 o’clock in the morning. The sounds of students repeating their lessons can be heard as we approach the school from a distance.

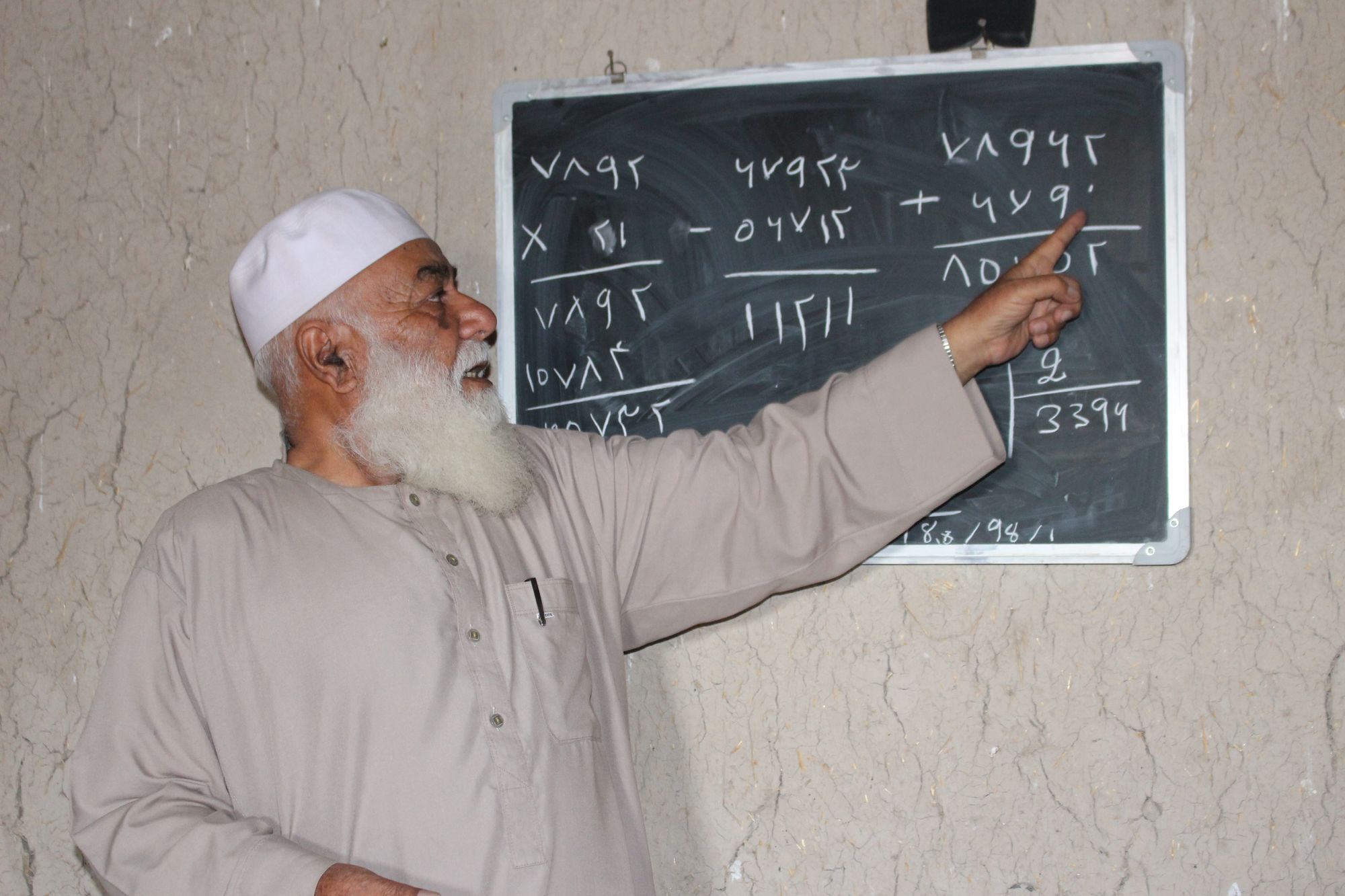

Mr. Jalalzai is busy teaching a group of students as we enter the school. His white, slightly combed beard nearly matches his white skullcap. Ghawsuddin’s warm, welcoming presence would not alarm even the most skittish creature. He gestures with one arm, welcoming me into the school before enveloping me in a warm hug, and introducing the other teachers; Engineer Bashir, Nasibullah, Noor Mohammad, and Ezatullah, all of whom teach at the school voluntarily.

All of the teachers keep a second job in order to make a living. Bashir is Mr. Jalalzai’s son, who tends his farms after class, Esmatullah is a tailor, Noor Mohammad an Imam, and Ezatullah owns a grocery store in Tarin Kot.

Ghawsuddin moved his family to Tirin Kot 10 years ago after securing his job as a teacher in the provincial capital. Located on the frontlines of the war between the Taliban and the previous government, his childhood home was used as a foxhole by the Taliban over seven years before the group regained control of the area.

After the previous government and its allies returned to the area his home became a target by ground and air forces whose troops shelled the home repeatedly over the years, completely destroying it.

After the Taliban takeover, Mr. Jalalzai rented a house from a neighbor for 5,000 Pakistani rupees per month ($24) to use for the school. A number of Afghan provinces trade primarily in a neighboring currency such as the Pakistani rupee or Iranian Toman. After four months, he could no longer afford the rent so he gathered the residents and spoke to them about the issue. Wakil Khodaidad, one of Jalalzai’s neighbors and a community leader, volunteered one of his houses for the school.

“The rental home had 10 rooms, enough for all our classes. We are currently housed in a six room home, which is why we had to say goodbye to around 200 male students,” Ghawsuddin tells Alive in Afghanistan during a tour of the school. At its peak, the school taught about 500 students.

The classrooms and shaded front balcony are filled with children focused on the blackboards and their teachers. Mats of different colors occupy the floors as children sit on them cross legged. A faded large steel bowl with the bottom missing is hanging on a copper wire from the ceiling that serves as the school bell.

One of the teachers asks his class about the previous lesson, most students lift their arms high and point their index finger towards the ceiling indicating that they would like a chance at repeating yesterday’s lesson.

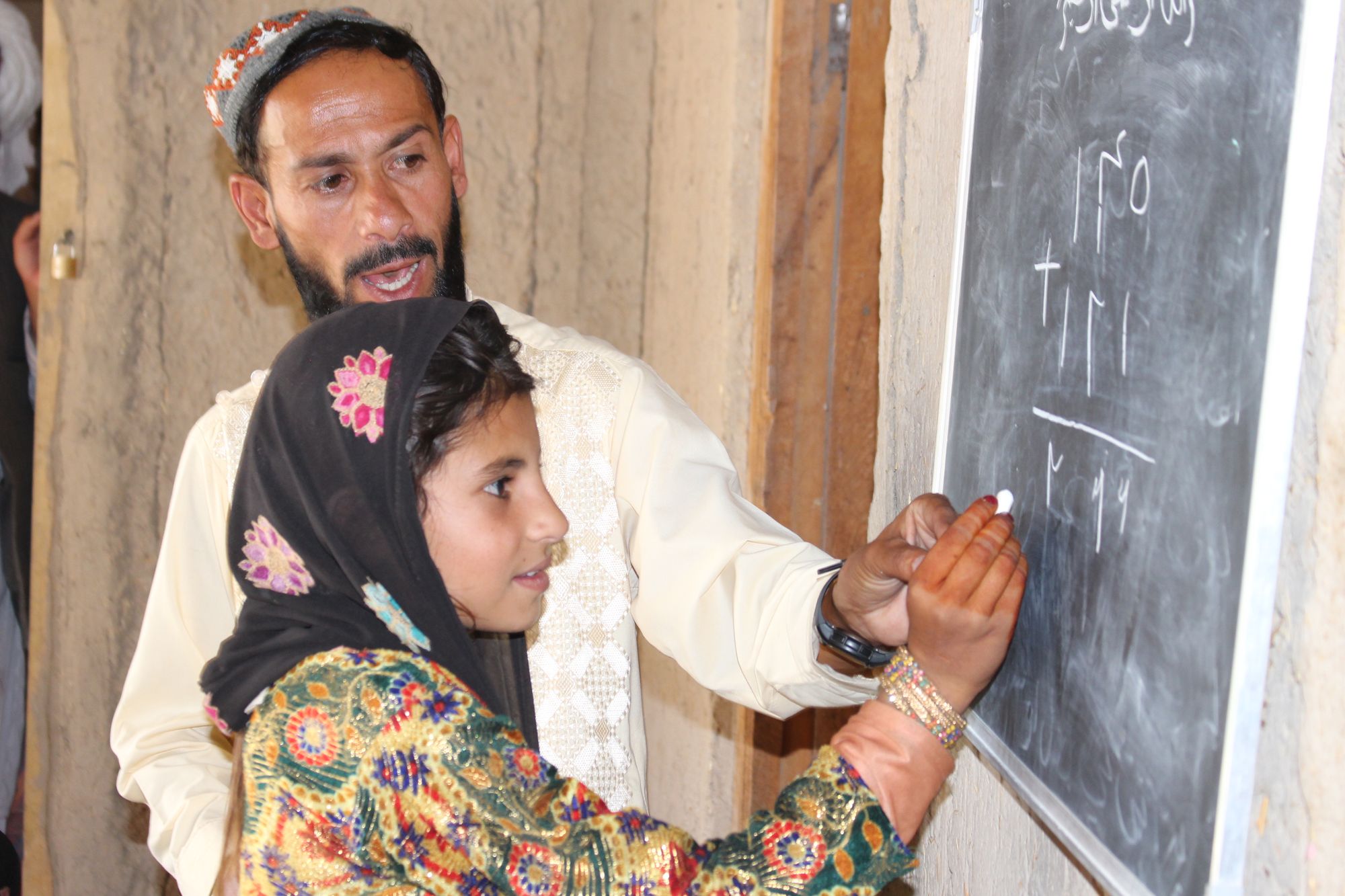

“Stand up,” Bashir Ahmad, asks one of the students, she comes in front of the class, takes a piece of chalk from the teacher and writes a math equation on the blackboard.

Everyone claps for the student after she solves the equation. She smiles and sits down, satisfied with her answer.

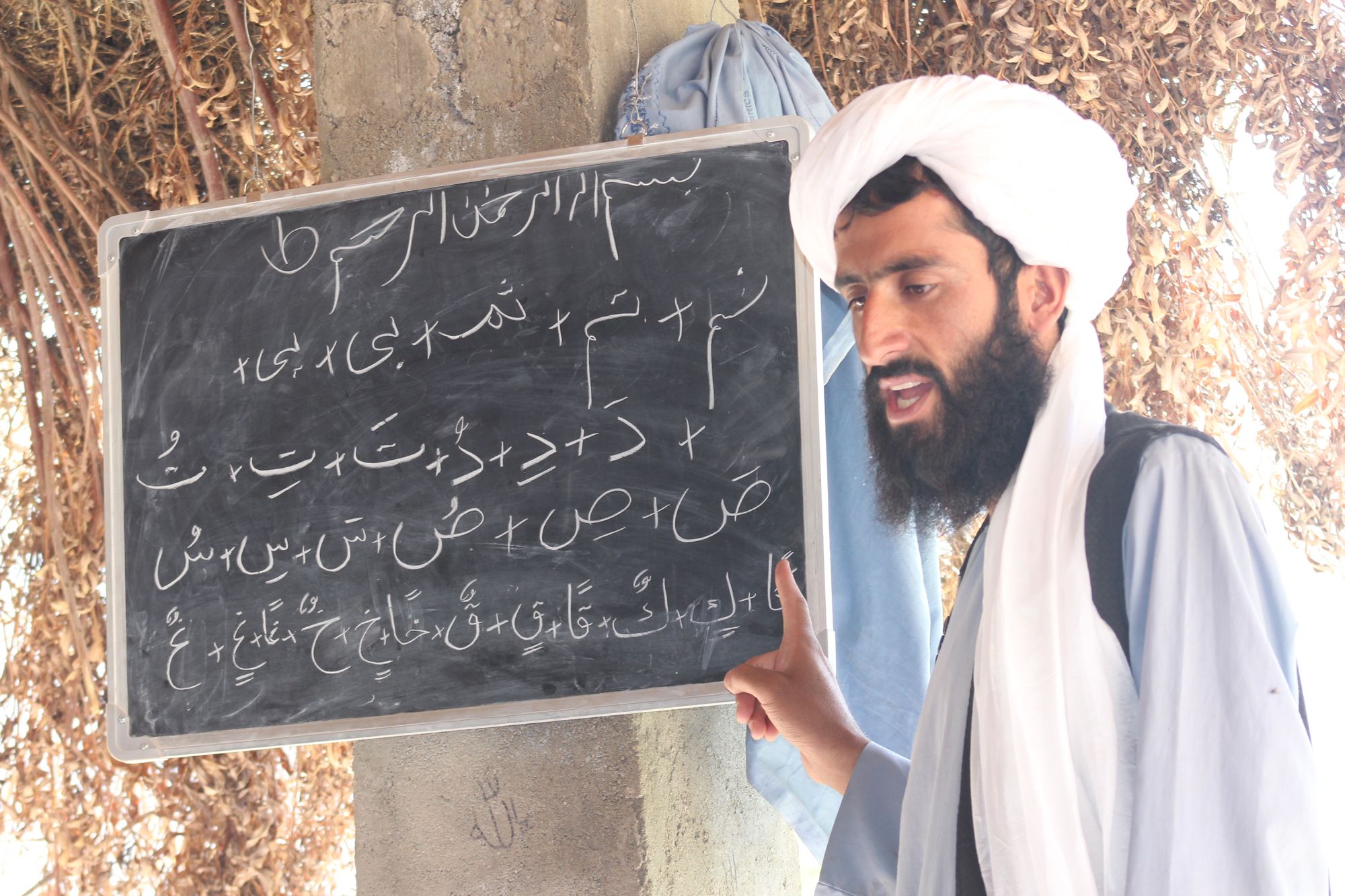

In another class, a teacher wearing a white turban teaches his students basic Arabic grammar.

“Ta,” Nasibullah says, pointing to the blackboard with the alphabets written on it.

“Ta,” his students repeat after him.

“Tay,” the teacher says,

“Tay,” the students repeat.

In the other class, students copy the math equations their teacher has written on the blackboard in their notebooks. Everyone is with their lessons, but the presence of a camera and journalist in the classroom–perhaps a first time for many of them–is more exciting than their lesson as they steal glances full of wonder.

According to Mr. Jalalzai, many families have a new interest in education. He says, “Many people bring their children here to register for school, but we cannot accept them due to lack of room and time.”

All of the teachers are volunteers who only have a limited amount of time they can teach each day. The school starts at 8am and runs for two and a half hours each day, six days a week.

“When we opened, no family would send their children to the school. We knocked on every door for two months and spoke to every family, telling them that we will teach religious subjects in addition to the usual curriculum, without charging them any fees,” Ghawsuddin says.

Many schools in areas controlled by the Taliban closed over the preceding years, due to the ongoing conflict and opposition to education within the community. The group banned education for girls above 6th grade citing both religious and technical issues. During their last rule (1996 to 2001), the Taliban banned secular education, replacing it with religious education, and they did not allow girls to go to school.

For more information on the situation of education in Afghanistan, please read Alive in Afghanistan’s articles on Education.

Currently the school only teaches up to 5th grade, but it will expand to include 6th grade once the students graduate 5th. According to Ghawsuddin, more than 90 percent of the students are children of Taliban members who could not go to school during the continuous war.

Mr. Jalalzai and other teachers are trying to register the facility as an official school, in hopes that they may be able to receive a salary and other amenities provided by the government to official schools.

I try not to disrupt the classroom as the teachers have only a limited amount of time they can dedicate to the students. Taking photos and videos, I go from one classroom to the other while the school is filled with the buzzing sounds of the students repeating their lessons back to their teacher.

At 10:30 sharp, Mr. Jalalzai rings the bell, signaling the end of the school day. Students flow out of their classes, heading home with the urgency of a rushing flood. According to parents who spoke to Alive in Afghanistan, when their children are dismissed from school the day is just beginning. Most students spend the rest of the morning and afternoon hours engaged in an array of tasks including farming and taking care of their chores around the house.

While the students are packing up their books to go I use the opportunity to speak with 11 year-old Hazrat Wali, a 4th grade student.

“I couldn’t come to school for several days because I couldn’t afford buying books and notebooks,” says Hazrat, “But our teacher, Mr. Jalalzai, sent another student to my house asking me to come back. When I came to school, they had bought the books and notebooks I needed,” Hazar Wali says, excited that he gets to continue learning.

Although I did try to talk to some of the girls and other male students, they shied away, refusing to speak.

Once the students had all gone home and school day was officially over, Ghawsuddin made some tea and we sat with some other villagers in the shade on the long porch that served as a classroom, talking about the school and its development so far.

“We first had to work hard to change the public view towards education,” Najibullah, a community leader in the area, tells Alive in Afghanistan.

“Mr. Jalalzai has guided the area towards a brighter future, and in doing so helped us tremendously,” Najib says.

The residents of the area who support Ghawsuddin and his team’s goal to get their school registered with the government hope the school will finish the process soon.

At 12:30 pm, Mr. Jalalzai’s phone rings– it’s a representative of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)-- while on the phone he tells the representative on the other end that the school needs tents and stationary. The look on his face when he hangs up suggests he did not get the response hoped for.

At 1 pm, we head to Ghawsuddin’s childhood home, which is now mostly in ruins. Signs of war and holes made by bullets clearly visible on the walls. We sit in one of the rooms that is still standing. Bashir, Ghawsuddin’s son picks some fresh fruit from their garden that is adjacent to their house and brings it over with yogurt and bread to be served as lunch.

After lunch, I depart back to Tarin Kot as Mr. Jalalzai leaves to get his materials ready for the next day’s lessons. On my way home I can’t help but wonder how he has such hope that he can bring change within a community marred by years of war, where his childhood home and the bullet holes that cover the walls remain a testament to the work that remains to be done.

If you are able to support our work financially, please click the button below.