Reading Poetry on the Longest Night

Shab-e Yalda celebrates the longest night of the year, it is an important festival for Afghan, Iranian, Tajik, Kurdish, and Azeri communities, regarded as a time of blessings and the resurgence of love and the sun.

Written by Shabana Farahmand

ESHKASHIM, BADAKHSHAN — Shab-e Yalda, also known as Yalda Night or the winter solstice, is an age-old festival celebrated in Afghanistan, Iran, and Tajikistan. It begins at sunset on the last day of autumn and lasts until dawn on the first day of winter. The occasion commemorates the longest and darkest night of the year, steeped in historical significance.

The term "Yalda" originates from the Syriac language and translates to "rebirth." Throughout history, this night has been regarded as a time of blessings and the resurgence of love and the sun. Notably, the Iranian scholar and polymath Abu Raihan Al-Beruni also subscribed to this belief.

During the Sassanid era, when Zoroastrian and Mithraic religions were prevalent, the winter solstice began at the start of the Jaddi, the third week of December. From that point on, nights grew longer while days became shorter. Believers considered this phenomenon a representation of the emergence of light and the waning of darkness, reflecting the dualistic philosophy of the time.

The festival continues to be practiced in regions that were once part of Ariana, Persia, and Khurasan, today’s Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

To document the celebration of the winter solstice and the rituals practiced in Badakhshan, a province in northeastern Afghanistan, I visited the home of Frishta Sadid, a resident of the area. Frishta graciously allowed me to take photos of the festivities but requested that I refrain from photographing those celebrating the night due to security concerns. Frishta lives with her parents, one brother, and seven sisters.

At Frishta's home, I find her family and friends gathered for the evening celebration. The women were dressed in stunning Eshkashimi and Sheghnani dresses, which showcased the beauty of their hometown. Eshkashim and Sheghnan are two districts in the province of Badakhshan.

The celebration is centered on a table adorned with a white tablecloth, embroidered with a striking green and red floral pattern. The table is covered by pomegranates, watermelons, apples, dried nuts, and sweets, all chosen specifically for the occasion. Candles flicker in the background, creating a warm and inviting atmosphere. Nearby, a pitcher, a clay mug, and several teacups are arranged, inviting guests to pour themselves a cup of tea and join in the festivities. The room is filled with the sound of joyful chatter as loved ones come together to celebrate.

As I admire the beauty of the table setting, Frishta shares the message of Yalda with me: 'There is light after darkness, spring, and blossoming flowers follow every rough winter. The same is true about life - good days follow difficult seasons, so we shouldn’t lose our hope,' she says. Her words carry a deep sense of optimism and resilience, reminding us that even in the face of hardship, hope can prevail. Yalda's celebration serves as a reminder of this message and the importance of coming together with loved ones to share in the joy and hope of the occasion.

Frishta continues, “The different types of fresh and dried fruits, alongside poetry books by Rumi, Hafez, and Saadi are part of the unforgettable night’s ritual. Pomegranates and watermelons take center stage during Shab-e Yalda, as elders believed they symbolized welfare and abundance. The high number of seeds in pomegranates and the red color of the watermelon symbolize the sun and happiness. Candles are used to light up the dark night, creating a warm and welcoming ambiance. Poetry readings from Mawlana, Hafiz, and Saadi are used to tell fortunes and keep the ancient tradition alive.”

As Frishta’s friend Rohina flips through the pages of Hafez to read the poems, she says, “We gather around with friends and relatives to celebrate this ancient tradition every year. We wanted to make the event special by having colleagues, friends, and Frishta’s kind family with us. In a time when we often hear less than positive news, and when doors seem to be closing for women, we saw the celebration of Yalda as an opportunity to reduce some of the sadness and soothe each other's souls.”

As Frishta begins to recite a poem by Mawlana, the atmosphere in the room becomes even more poetic and lovely. It's then that I notice a small bookshelf in the corner, dominated by books by Mawlana and Hafiz.

On one wall of Frishta's cozy home hangs a beautiful painting of Mawlana, set against a stunningly painted background. In Nastaliq script, the word 'Nothing' is written alongside the figure, adding a touch of mystique to the already intriguing artwork.

“Really, why poems by Mawlana and not Hafiz or other poets?” I ask.

“Because I like Mawlana’s poems of love. He sang from the heart, putting all he had into love, Mawlana has short but very meaningful poems. Every single word in his poem is rich in meaning and full of emotion, that’s why I love to read Mawlana more often,” Frishta replies.

Shab-e Yalda is celebrated throughout Badakhshan. However, in Eshkashim, they add their unique twist to the festivities. Along with the usual amenities, they prepare and serve Badakhshan's Shor Chai in a special teapot and use family heirloom lanterns and clay dishes, which add to the celebratory ambiance.

Badakhshan is famous for its Shor Chai (salted milk tea) and Badakhshi cookies. Shor Chai, a tradition in northeastern Afghanistan, is a variation of milk tea. However, instead of using sugar to sweeten the tea like in India and Pakistan, people here add salt and crushed walnuts to it. The first and second sip can be a little hard for some people to appreciate but by the third sip, one gets used to the taste and it is quite delicious.

The room is decorated with traditional musical instruments such as Tanbur and Qashqarcha, which are unique to Afghanistan's northern region. These instruments will be played throughout the night to entertain the guests until the sunrise of the following day.

Surat Mah Kashani, dressed in a unique red attire from her region, says, "We celebrated Yalda as we have done in previous years, by making and wearing traditional clothes. We will read poems, enjoy fruit, get our fortunes told, and recount tales of the past."

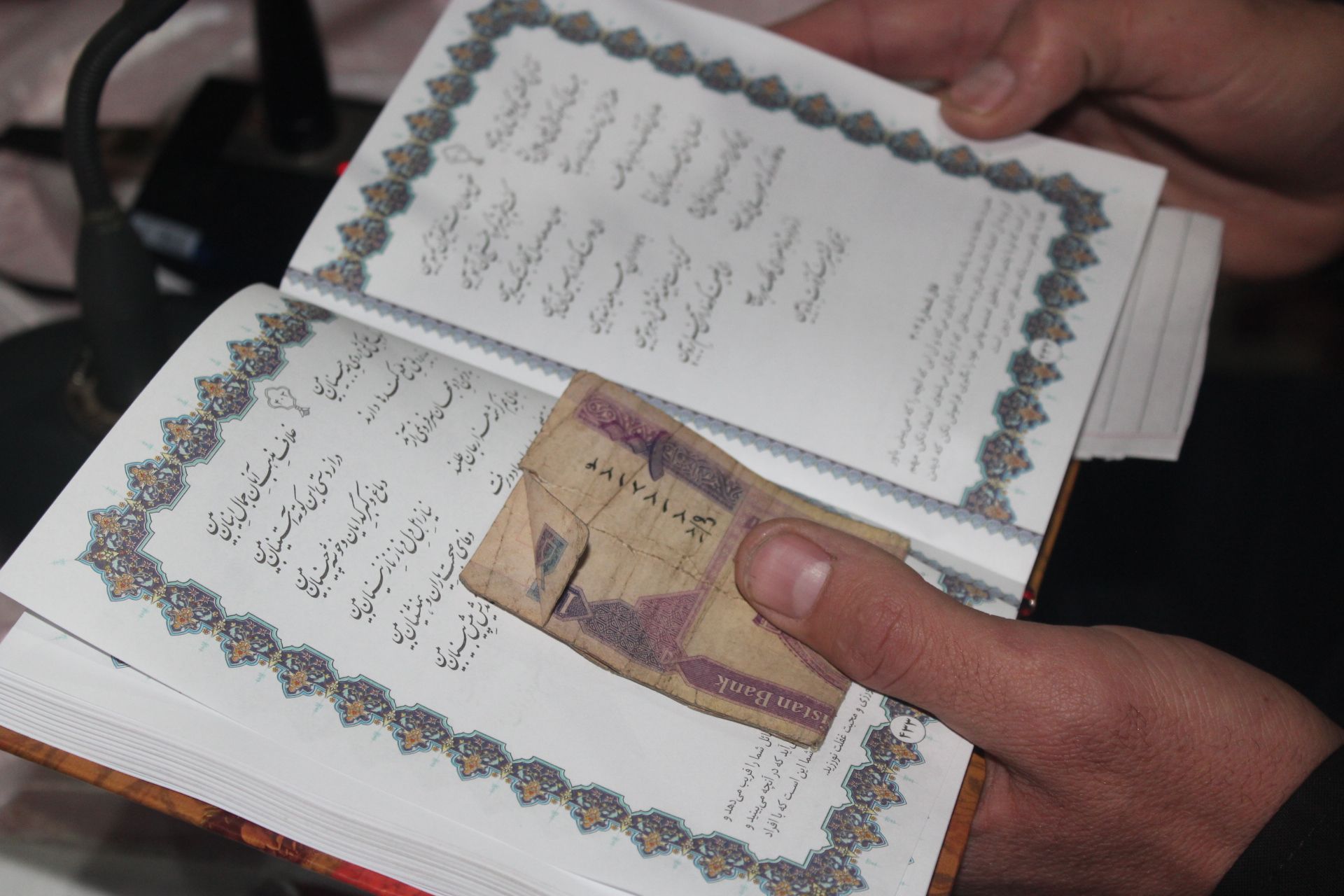

Gulalai, a 70-year-old woman sitting in the corner of the room, is holding a copy of 'Fortunes of Hafez' in her hand. She inserts a 100 Afghani ($1.12) bill between one of the pages and says, "Reading your fortune on Yalda is a long-standing ancient tradition, primarily intended for amusement and entertainment."

Gulalai flips through the pages of the book to the section with fortunes, makes a wish, and selects a number. She then turns to the corresponding page and reads her fortune aloud, with everyone taking turns after her.

If the fortune is favorable and positive, the person whose fortune is being read must pay 100 Afghanis ($1.12) to the fortune teller (the person reading the fortune from the book of Hafiz).

"When I was 20, I celebrated Yalda in the same way as I do today - by reading our fortunes and listening to sweet tales and stories from our grandparents. Now, as a grandmother, I share stories of the past with others," Gulalai reminisces.

Amid the tense atmosphere enveloping Afghanistan after the Taliban's return to power, observing these traditions has become a means for women and cultural activists to spend quality time together in a friendly environment.