Journalists on the Run

On World Press Freedom Day, Alive-in published an article about Safia Ishag, a journalist fleeing from Darfur. This follow-up article focuses on two more journalists, Hafitha and Ezaldeen, both of whom spoke with Alive in Sudan from Uganda.

reporting by Entesar Abdallah

assembled by Logain Ali and Brian Conley, with assistance from the Alive-in/ editorial team

This story is part of a partnership between Alive-in/ and DT-Institute to support Sudanese journalists inside and outside Sudan. DT Institute is both a funder and an implementer of peace and development projects. More stories can be read in Arabic on the Alive-in/Sudan Facebook page.

Alive-in is a not-for-profit media agency that mentors journalists from underrepresented communities to increase local and national understanding.

If you are able to support our work financially, please click the button below.

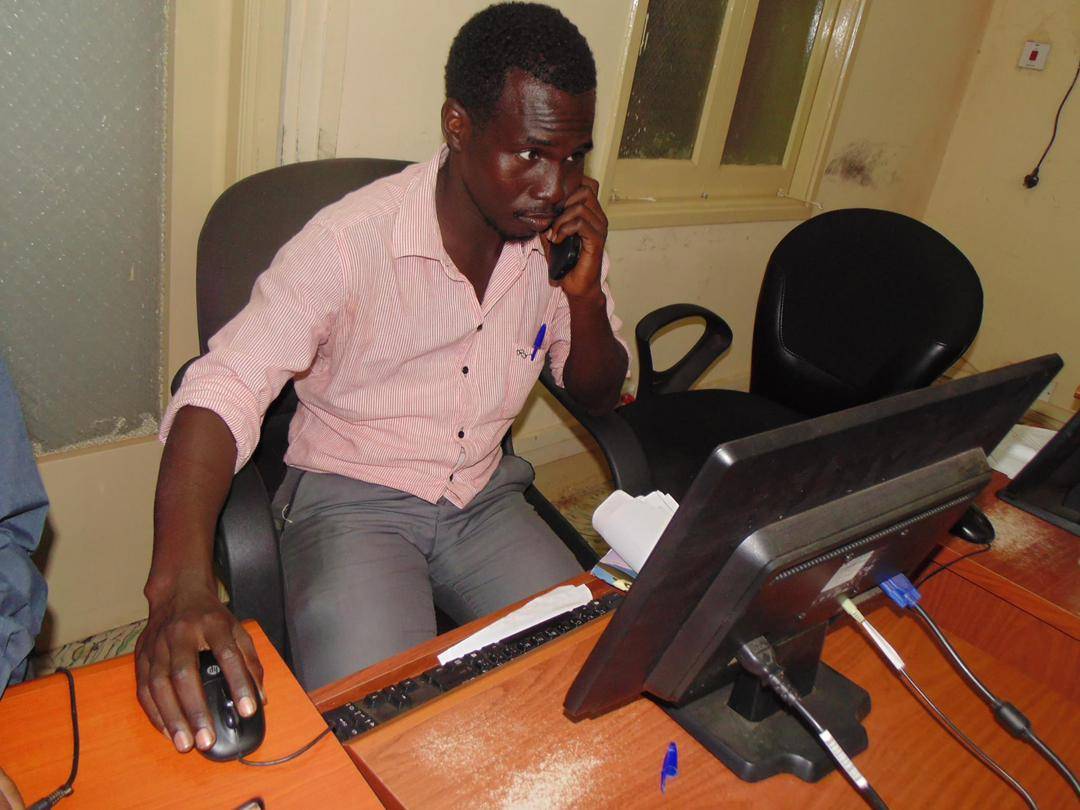

KAMPALA, UGANDA—Many journalists currently in Uganda wish to return to Sudan for various reasons including financial hardship. Alive-in/Sudan spoke with a displaced Sudanese journalist, now residing with his family in Kampala, Ezaldeen Arbab who said, “The situation for a lot of the journalists here is very dire.”

“Currently there are many who are in contact with me saying they are unable to pay rent, and don't know what their next step is going to be. Some are thinking about going back to Sudan, no matter what happens. Others went to the refugee camp, where they get shelter in a tent, they have no other way.”

Ezaldeen is a freelance journalist from El-Fasher, Northern Darfur who covers climate change, migration and issues related to refugees. Ezaldeen arrived in Kampala with his wife and children in July last year. He recalled, “I stayed under the bed for three, four, five days, and when a whole week passed, we were entirely besieged, the shelling was everywhere.”

Alive in Sudan met with another journalist from Zalingei, Hafitha Musa, in Central Darfur earlier in March of 2024. She writes about everyday life and challenging circumstances in Zalingei, some of which resulted in her receiving threats. As a result, the interview was conducted at an undisclosed location in Kampala. She too had to flee her home.

Journalists and human rights activists have been routinely targeted in Sudan, not only in this conflict but in previous ones going back decades. Many of these conflicts originated in Sudan’s western Darfur region. Hafitha was arrested in 2022 for covering vegetable sellers’ demonstrations against the planned relocation of the vegetable market in Zalingei.

Perched on the edge of a bed in her sparsely furnished room in Kampala, Hafitha spoke slowly, and with purpose, betraying a sense of nervousness as she recalled her long journey from Darfur to Kampala.

“There were many reasons that pushed me to leave Darfur and migrate. I never imagined leaving Sudan or Darfur one day. What made me consider leaving was the numerous events related to my profession, including harassment, threats, and the lack of security..”

In the early days of the war, Zalingei became a focal point of intense fighting in Western Darfur. Trapped in the crossfire between the warring factions, many residents were compelled to abandon their homes. The Hasahisa camp in Zalingei, which has sheltered more than 50,000 people since 2003, is now the source of reports recounting horrific stories from the besieged area, as the RSF is blocking humanitarian aid from reaching the residents.

“The journey was extremely difficult. From leaving Darfur until I reached this place, the period was very long, about a month and two days. I walked according to the circumstances that happened to me.”

According to Hafitha, “We traveled by bus and sometimes in small cars, depending on the circumstances of the area we were in. The bus we were in was looted four times. The unfortunate thing on the road is that there were beatings, threats, looting, and death.”

Like many refugees, Hafitha had not initially planned on traveling to Uganda. She told Alive in Sudan, "I was just hoping that if I reached a safe place without repatriation or harassment, I would settle there. Suddenly, I found myself in Kampala, Uganda."

Safer, but not without challenges

There have been multiple waves of displacement since this most recent war began in April 2023. When fighting broke out in El-Fasher during April of last year, Ezaldeen arranged for his mother to go to live with his sister in Libya. However, his mother passed away during the harsh, unforgiving journey. Anxiety and mental anguish characterize Ezaldeen Arbab’s escape from Sudan.

He mentions the prevalence of armed men which caught his attention. “For hundreds of kilometers, at any moment, an armed man can arrest you and kill you without any reason, you no longer feel safe, it is the worst feeling.”

“The war caused us mental problems and trauma. Even the children, when they hear the sound of a plane in Kampala, they panic.”

Air raids have been a feature of the latest conflict in Sudan since its earliest days. The Sudanese Armed Forces have been accused of not protecting civilians during air raids against Rapid Support Forces that the army claims are embedded within the population. Since the war broke out in April of last year hundreds of civilians have been killed by aerial attacks, if not more.

Safia Ishag, who spoke with Alive in Afghanistan previously, also fled to Uganda for safety after having to escape for her life.

Although long a haven for refugees from South Sudan, both Safia and Hafitha expressed experiencing great difficulties in Kampala. Although away from the conflict in Sudan, they faced new challenges. In Safia’s case, she said she was at least somewhat prepared and knew what to expect.

“Before I came, I did some research and found out that there are also difficulties in living here and real suffering for young people because there's no work and [nothing to do]. Even if you want to start a business, there's no organization to fund you. You need someone to finance you so you can continue your life normally.”

For Hafitha she felt more comfortable in Kampala, telling Alive-in/Sudan, “I feel a kind of comfort and stability. It's a country that has accommodated many foreigners and refugees, which is a very great thing for a country like Uganda to accommodate you in the midst of a major crisis. I feel happy that I have come out of gloomy situations like the ones in the past.”

However, although her situation is better, she still hasd concerns, saying, “Despite being in a very safe place, I am worried about [my] family and relatives in the ongoing war.”

Since fleeing their homes neither woman has been able to continue working as a journalist.

Hafitha said she cannot work because, “All the devices I owned were looted, including the camera, laptop, and recording devices. I have nothing to work with. Even with the phone, I could work, but I can't. Why? Because the materials I have with me are related to violations and focus on certain sensitive issues. I have a passion to work, but I can't due to concern for my safety.”

According to Safia, the newspapers she worked with before are currently closed. She told Alive-in/Sudan that although she was supposed to receive her last salary on Eid, so far she still has not received anything. “We're on unpaid leave, jobless, and without any means of livelihood.”

Despite all the challenges, Hafitha intends to go back and continue her work as soon as possible. “If the country gets better, of course, it will need us, and we must return. If the war stops, God willing, I will be one of the first to come back.”

Hafitha soon had to move from the hostels in Makarere Hill to one of the camps set up for refugees in Bewyale, Uganda, because of the deteriorating economic conditions and the harsh circumstances of having to start anew.

As a freelancer, Ezaldeen says the pay isn’t consistent or sufficient to start a new life and meet his family’s needs. “If you want to work on stories from Sudan, it's a bit difficult. It's possible, but a lot of institutions require your presence within the country, that is what's hard,” he added. “Secondly, the future remains unknown, people here are complaining about the increasing expenses in regards to rent, healthcare, and the anxiety of it all.”

Struggling to Stay Connected

The ongoing conflict has impacted communications for millions across the country with territorial clashes worsening. For Hafitha, Safia, and Ezaldeen, they continue to wonder about their families in Darfur as the RSF’s stronghold over the region intensifies.

Telecommunications networks had been abrupt since the beginning of the war due to the total destruction of towers and other communication infrastructure during the hostilities between the army and the militia.

“I have been able to communicate with my sister but not my parents. The network is slow and it takes two hours to send a message. They have to climb up the mountain where there are snakes and things like that. I tell them, if you find time and money to go to the Wi-Fi, you may connect for half an hour. Maybe I can send voice notes to my parents and receive voice notes about their news. That's it!” Safia tells the Alive-in Sudan reporter.

In February, a nationwide telecommunications blackout posed significant challenges, hindering communication, and restricting access to financial resources and support systems, including the alarming obstruction of humanitarian aid from reaching those in need. This added insult to injury after Al-Burhan (leader of SAF and Sudan’s de Facto president) blocked aid from entering RSF-controlled regions compounding into grim outcomes and warnings of famine.

According to an unpublished investigation carried out by Ataf Mohammed, editor of Al-Sudani–a local independent newspaper–the RSF was responsible for the blackout in an attempt to “twist the army’s arm”. When deemed unsuccessful, they decided to exploit the Sudanese populace through the sale of internet services against a fee.

When asked about how he communicates with his family, Ezaldeen told the Alive-in team, ”We usually communicate via Starlink, but currently, the network is working. However, when the networks go down, we switch back to using Starlink.”

Unfortunately, for the millions affected, the only alternative communication options were through informal providers of Elon Musk’s Starlink services, many of whom are affiliated with the RSF.

“The RSF has completely taken over the area, they brought in their own devices, since all the networks have been damaged. My family checks on me once or twice a week,” Despite Hafitha’s family circumstances, having to shelter, she continues, “They are economically devastated, and each of them takes significant risks to gather 2,000 Sudanese pounds to be able to check on me for half an hour of internet services”.

Although, SpaceX (operator of Starlink internet services) announced it would cease operations in Sudan effective April 30, pleas from humanitarian rights organizations condemning the potential shutdown as “collective punishment” appear to have delayed the termination process.

Back home, the conflict continues

In addition to the challenges each of these journalists face, the news back home continues to worsen. Reports from El-Fasher in late April 2024 have been deeply troubling. The U.N Security Council has issued a stark warning of an imminent attack on the capital of North Darfur as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have encircled the city, the last one in the region not under its control. Due to its strategic location, El-Fasher is considered a crucial territory, and significant civilian casualties have been reported since the fighting began. The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) have called in reinforcements to ensure the city does not fall to its opponents.

“Once we left El-Fasher, the RSF stopped to interrogate us and the driver, we don't know what he said to them, but we then arrived at Alkoma locality, there we met armed men, we couldn’t identify which side they were affiliated with and we couldn’t object because we risked being robbed. Their leaders told us the road ahead wasn’t safe and they forced us to spend the night.”

Although the region has witnessed ethnically-motivated violence, perpetrated by the notorious Janjaweed militia more than 20 years ago, its troubled past has not been left behind, with the Janjaweed having been rebranded as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in 2013. Despite the near-indistinguishable differences in appearance between people of African and Arab tribes in the region, the RSF has launched a brutal campaign against so-called non-Arab communities.

Ezaldeen explained that people are targeted based on their skin color and ethnicity, “If you are from a specific geographical area, you are deemed suspicious. For instance, if your national identification number indicates South Darfur, as some Darfur tribes are members of the Rapid Support Forces, individuals from these areas face stricter scrutiny. Therefore, in a Rapid Support Forces base, someone from certain regions may be viewed with suspicion.”

The escape from El-Fasher was not without difficulty for Ezaldeen and his family - the economic exploitation and price gouging of goods and services in Sudan has also exacerbated the situation for those trying to sustain themselves during the ongoing conflict and those attempting to leave. Izzeldin says, “There is lack of security, financial difficulties, and people took advantage of the war and prices increased, whether it was in travel, food, or governmental procedures.”

Ezaldeen describes his 20-day journey from El-Fasher to Kampala as “The worst and most difficult trip of his life.” Ezaldeen and his family boarded the bus from El-Fasher’s AlMawashi public market, taking the Kosti Road to Omdurman.

Ezaldeen initially intended to take the Kosti road to Renk, because it was the more moderately priced option. However, he reconsidered his plans as he was worried about it being too hot for his family , had he traveled through South Sudan. However, the road from AlGallabat to Ethiopia came with its own set of obstacles.

In order to cross to Ethiopia, Ezaldeen had to acquire security permits, which meant he needed a guarantor in the city of Gadarif, he describes this as an impossible condition for any traveler saying, “It was a very long and slow process, once it was done, we left for the border crossing, and headed to Ethiopia.”