Hopeless Brides and Refugee Grooms

#Afghan women lament the exorbitant dowry amounts incurred after their engagement, saying “absurd” cultural norms create a variety of issues, including domestic violence and termination of their marriage.

Editor’s note: Interviewees requested pseudonyms to conceal their identities for safety due to the sensitivity of the issue covered in this article. The precise location of the interviewees, including the name of their village and district has also been redacted for safety purposes.

Written by Zarghuna Akbari

JAWZJAN, AFGHANISTAN — “If I [ever] have a daughter, I am going to leave the dowry for them to set, and not sacrifice their happiness for our absurd traditions,” said 28 year-old Shigofa, a female native of northern Jawzjan province, who has been married for a year.

Shigofa is one of five women in different marital stages Alive in Afghanistan interviewed across Jawzjan province. Each lamented this cultural norm, saying the expenses and exorbitant dowry amounts are significant burdens for their grooms and a source of concern for individuals wishing to get married.

In Islamic tradition, the Mahr or dowry is a gift or a promise of a gift to the wife by the husband, which the wife can demand at any time in their relationship, and the husband must pay the amount demanded. However, in Afghanistan, the dowry is seldom given to the wife and is instead spent by the woman’s family as they desire.

“Sheer-baha”, “gala”, and “jaheezia” are terms used for bride price, an amount charged separately from the dowry by the women’s families in some regions.

Although Afghanistan’s economy has been in a nosedive since the Taliban takeover of the country, the economic collapse has had little impact on cultural norms and traditions that have negatively affected the lives of many.

According to the women interviewed, a majority of women are against exorbitant dowries but have little influence in the decision-making process. This is because engagement, marriage, and the entire process is controlled by men in Afghanistan’s male-dominated culture. The women being married off to potential suitors have little to no say in either who their future partners will be or what the bride’s families will demand from their suitors.

The five women say the expenses and exorbitant dowry amounts are significant burdens for the grooms and a source of concern for young men wishing to get married.

“The excessive dowry amount and extravagant expenses are truly an injustice and coercion,” Shigofa said, before adding that the issue, “Diminishes affection among families.”

The issue drives many engaged men to undertake long journeys away from their homes and family. The men are often forced to work abroad for years to accumulate sufficient funds for the dowry and a variety of expenses following their engagement. In most cases, the dowry must be settled before the wedding ceremony.

The extended period of hiatus and struggle to accumulate the necessary funds may lead to delays in marriage, consequently resulting in subsequent issues and instances of domestic violence.

Shigofa expressed frustration with this tradition that has caused many individuals to borrow money from friends, relatives, or banks. These loans have left many grooms burdened with debt long after the wedding takes place.

Shigofa’s husband had to borrow 480,000 Afghanis ($5,457) from relatives and banks to cover her dowry and their wedding expenses. According to Shigofa, her husband purchased 200,000 Afghanis ($2,273) worth of gold, some of which he resold to pay back his debts following their marriage.

“My husband has a good job, but he borrowed so much that we are still in debt. I didn’t agree with the expenses, but my family asked my husband for a wedding and expenses similar to those of our relatives,” Shigofa told Alive in Afghanistan, adding that families demand expenses similar to or over the set amount among the region or the ethnic group.

The lavish ceremonies, extravagant gifts, and exorbitant dowry amounts are used to flaunt the ability and newfound wealth of the womens’ family among their relatives. “So other people would say that the family bought a lot of goods, carpets, dishes, and gold for their daughter with her dowry.”

The womens’ families also use the dowry to purchase household items for the women to take with them after their wedding.

Fatima Mohammadi, another native of Jawzjan, has been engaged for three years. Her dowry was set at 600,000 Afghanis ($6,862), of which her fiancé has managed to pay only one-third thus far. This amount does not cover the costs associated with the wedding ceremony or any other expenses during their engagement, which can be quite substantial.

Despite Fatima's opposition to the excessive dowry and the significant expenses related to her wedding, she lacks any influence or control over the matter.

"Our society is male-dominated and patriarchal. My opinion regarding the dowry, wedding expenses, and how the wedding ceremony is held has no significance. Just the fact that they asked me if I accept this boy as my husband or not is a significant statement for me. In other words, we don't have the right to interfere at all because our culture and society do not allow it. We are completely silent on these matters and do not have the audacity to talk about them," Fatima told Alive in Afghanistan.

According to Ms. Mohammadi, when girls voice their opinion regarding their dowry or expenses related to their relationship, they are unjustly labeled as "shameless" by their relatives, a method used to silence any objection from women.

“There are a thousand other expenses in addition to the dowry,” Ms. Mohammadi said, “From Eidi (clothes and jewelry given to the bride by the groom’s family during Eid ceremonies while the couple is engaged) to sacrificing sheep. Although families know the dowry belongs to the daughter, they never give it to her. They take the money from the groom and spend it on whatever they desire.”

Fatima believes that these overwhelming expectations have taken a toll on her fiance, and the prolonged postponement of their marriage has subjected her to ridicule from her relatives.

Khurshid, another resident of Jawzjan, has been engaged for two and a half years. Her fiancé, who was working at a bank before the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August of 2021, initially left to work in neighboring Iran to save for the dowry, set at 500,000 Afghanis ($5,718).

According to Khurshid, the delay in their marriage as a result of the high dowry amount, and lavish expenses demanded from the groom’s family during the holidays has increased the distance between both parties.

“I know that the dowry is my right, and so does my family. I can’t talk to my father about it, but I keep asking my mother to stop [the groom’s family] from bringing gifts [during Eid] and lower the dowry. However, my mother says that my father is the decision-maker in these matters, and lowering the dowry will also mean ridicule from other people,” Khurshid told Alive in Afghanistan.

Khurshid laments her family’s decision to force her fiancé to buy land and build a new house for the couple in Shiberghan, the capital of Jawzjan province, as one of the terms of their relationship.

“My fiancé bought a piece of land for 380,000 Afghanis ($4,346) and built part of the house with money he earned in Turkey [where Khurshid’s fiancé currently works and traveled to after Iran], but our relationship has become colder by the day. He no longer intends to return, and due to the increasing issues between us, we don’t even talk once a week, and I often think about breaking off the engagement,” Khurshid said, adding that the mounting costs shattered their hopes and dreams as a couple.

Khurshid states that the future of their marriage is currently uncertain. She is unsure when or if her fiancé will be able to cover the expenses and return to Afghanistan.

Mahbuba, who is a member of the Turkmen tribe, told Alive in Afghanistan that her tribe demands the highest dowry of all ethnic groups in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan’s Turkmens are predominantly located in the northern region of the country.

“Our families take a little money they receive from the groom [and his family as dowry] and spend it on us [purchasing household items for the bride to take to her new home during the wedding]. The majority of the money is used to buy land, spent on paying dowries for their sons, or buying livestock,” Mahbuba said.

Mahbuba has been engaged for over five years with a dowry of 700,000 Afghanis ($7,958). Her fiancé has been working in Turkey, earning 40,000 Afghanis ($454) per month, and has paid more than 500,000 Afghanis ($5,684) towards the dowry. Additionally, he has spent 300,000 Afghanis ($3,410) on various expenses since their engagement, as stated by Mahbuba.

Mahbuba said that only 200,000 Afghanis of the total dowry amount remain before the couple can get married. However, the wedding ceremony is expected to be extravagant, and the groom and his family are responsible for bearing the costs.

Afsana, another 28-year-old Jawzjan native, is still single due to her family's excessive dowry demands and the requirement for lavish engagement and marriage ceremonies, which potential suitors have yet to accept. While Afsana is aware of her rights as a Muslim woamn, she is hesitant to discuss the matter with her mother.

“In our society, especially in rural areas, women are not allowed to speak about their engagement or wedding. The elders of the family decide and determine the dowry. It has now become a tradition for the girl’s family to write down a list of expenses and a dowry amount, and present it to the suitors. If they [the suitors] accept, the engagement takes place, otherwise, [the girl’s family] say, ‘We cannot give our daughter to you unless you can afford the expenses!’” Afsana said.

According to Afsana, the list includes the amount of dowry, the quantity of gold or jewelry, and engagement, post-engagement, and wedding expenses.

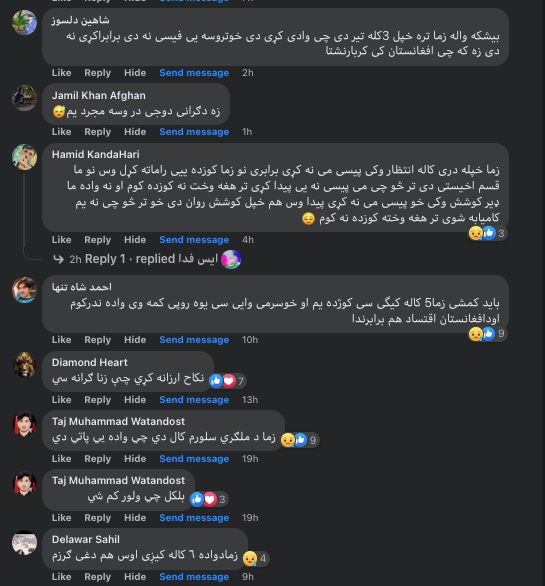

Following the publication of the Pashto version of this article, many commenters and Alive in Afghanistan Facebook followers expressed their concern and confirmed that either they or a friend they know has been working to pay off the dowry before or debts incurred after marriage.

Hamid Kandahari said, “I waited for three years after my engagement but couldn’t arrange to pay the dowry amount so my engagement was canceled. I took a vow to not get engaged or married again until I find the money.”

Ahmad Shah Tanha, another Facebook follower, said, “It [the dowry] must be reduced[!] I have been engaged for five years[,] but my father-in-law says he will not marry us until the last rupee [dollar] is paid.”

Delawar Sahil said he is still paying off debts incurred from getting married six years after his wedding.