Her Studio is Her Whole World

Diba Naseri’s world and her place of imagination is the tiny room she spends her time painting in. She is happy when she is painting, and nothing, not even the errors and mistakes in those paintings can take her out of her happy place.

— One Day in Afghanistan —

Written by Shabana Farahmand

FAIZABAD, BADAKHSHAN — Painting is an art form with a rich history in Afghanistan. Despite many ups and downs, painting has provided Afghans a means of expressing pain, depicting their culture, and disseminating new ideas and opinions.

Over the last two decades, Afghans had the opportunity to pursue art, including painting, as an official field in higher education. However, with the collapse of the previous Afghan government in August of 2021 and the Taliban’s return to power, many art fields, including painting, were no longer offered at Afghanistan’s universities. According to Islamic Hadith, only paintings of inanimate objects are allowed. Depictions of animated objects such as humans and animals may be considered as objects of worship or false idols, which are not permitted in Islam.

This week, Shabana Farahmand documents one day in the life of Diba Naseri, a 25 year-old visual artist in Faizabad, the capital of northeastern Afghanistan’s Badakhshan province.

At 10 in the morning, I arrive at my destination in Faizabad after a short car ride. Diba is a tall woman with large, almond-shaped eyes, embodying the quintessential image of an Eastern girl.

Diba’s house is in the heart of Faizabad, in the Shar-e Naw neighborhood. It is 10:30 in the morning when she brings me into her studio. The moment I enter the room, it’s clear that she is an exceptionally talented artist. Her fingers work like magic, infusing life and color into everything around her. Paintings in color and black and white occupy the walls of her studio, giving life to the dull, maize-yellow walls.

Diba holds a bachelor's degree in Law and Political Science and works as a teacher at a private school in Faizabad City. Diba learned drawing from Shafiqa, a renowned painter from Badakhshan, but it was through her own interest and unwavering dedication that she honed her skills in painting and drawing.

“I practiced drawing for 3 years. After the recent political changes in the country, I left the black and white world of drawing behind to experience the colorful universe of painting,” Diba tells Alive in Afghanistan.

Diba points towards a painting on the wall of her studio and says, “This was my first painting, which I completed last spring.” The painting depicts an Afghan woman in a burqa, with half of her face exposed and some of her hair visible, symbolizing freedom and captivity.

“When I finished my first painting, I had a strange feeling and couldn’t express my emotion in words, because I had expressed them in the painting with colors on the canvas,” Diba says.

Diba’s became an artist to reveal the stark, violent face of society. “My aim is to show the violence against women and children in Afghanistan through my paintings. My portraits primarily depict violence against women while my landscape paintings convey a sense of delicacy and beauty,” Diba says.

At 11 in the morning, Diba brings a large tray full of dried nuts and fruits, a tasty cake, and green tea. Hospitality is the most beautiful custom among Afghans across the country, something you will experience wherever you go.

“So far, no one supports me financially. I taught at Burna private school while I was getting my bachelor's degree. I buy the paint, brushes, canvas, oil, and all the other painting tools with my own income, and they are pretty expensive. One meter of painting canvas costs 800 to 1,000 Afghanis ($8.93 to $11.17). A small box of paint costs 150 Afghanis ($1.52). Another problem is that oil paint is scarce in Badakhshan, I primarily order them from Kabul. I never use my income to buy clothes, shoes, or headscarves for myself,” Diba says.

While I’m with Diba, one painting in particular grabs my attention. She explains that it was a recent creation of hers and adds, “This painting portrays my imagination of the current status of women [in Afghanistan] and the concept of freedom.” In the artwork, black crows with eyes are shown building chains and cages, while doves without eyes are depicted flying and breaking free from the chains.

“This piece conveys the message of freedom and showcases the conviction of women in fighting the increasing limitations on their mindset [by society],” Diba says.

After having lunch and performing prayers, we resume talking while Diba paints a portrait of Charlie Chaplin. It is now 1 pm.

“I’ve been working on this piece for a few days now and I am going to finish it today. I am painting it for my brother-in-law and because he is very fond of Charlie, I will give it to him for his birthday,” Diba says. Diba admires the work of Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Leonardo da Vinci. Diba’s favorite artist is Van Gogh, who, according to her, paints based on his imagination, a style Diba follows and calls “Modernism”.

“I have painted and drawn more than 1,000 pieces so far but I have to say that I can never discriminate between my art because I have poured my feelings and emotions into them,” Diba says.

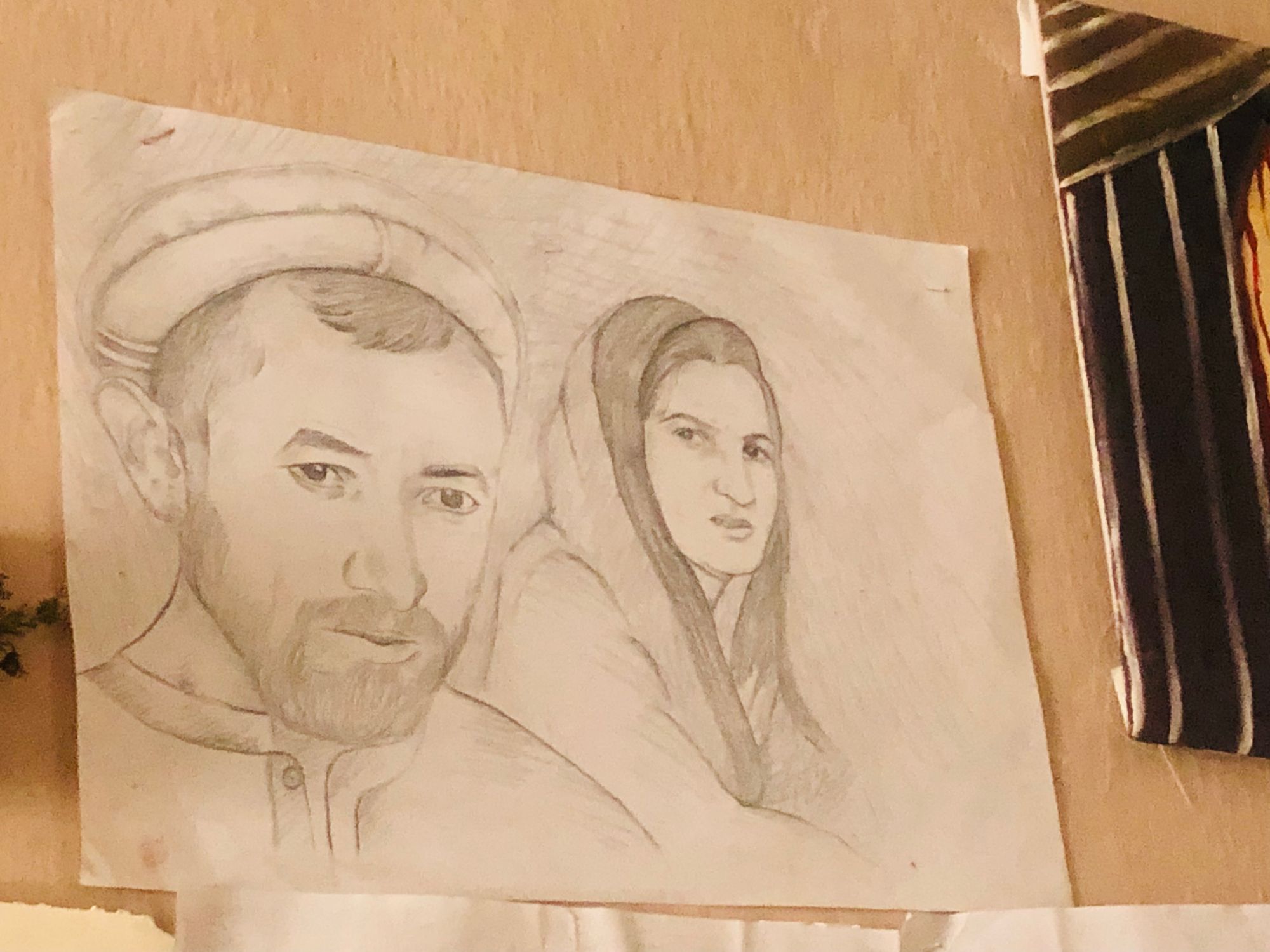

It is now 2 pm. A drawing of a man and a woman in the highest row to my left catches my attention. Diba sighs and says, “That’s my parents, I drew this in the early days of my work.”

“Life is full of tragedy. I am reminded of my father whenever I see this portrait. My dad used to make me tea every afternoon after I returned from school. I was really interested in singing when I was in grades 7 and 8. One winter, he took me to Baharak district and bought me a big MP3 player. I would play music on it all day and practice singing. My dad bought me a Rubab (an Afghan musical instrument) from Eshkashem district after realizing my avid interest in music. He also spoke to a neighbor to teach me how to play the Rubab. I was only 13 back then. Due to issues and gossip, after a year I couldn’t continue playing,” Diba tells Alive in Afghanistan. Conservative Afghans consider music sinful, and as such, anyone playing an instrument or singing is committing an act of sin.

Diba continues affectionately talking about her late dad and his support of her education. Her father’s insistence on and financial support for her continued education got her to get a bachelor’s degree in law. According to Diba, her father used his pension to send her to a private university in Faizabad, where she now teaches.

Diba’s father passed away due to an illness 3 years ago. She requested to not share more details about the event or the cause of her father’s demise.

Diba doesn’t make an income from her paintings. “My goal since the beginning hasn’t been to make a living out of the paintings because the artform doesn’t really have any potential income in Afghanistan anyways. My emotions also won’t let me sell my feelings and spirit [which I have poured into these paintings],” Diba tells Alive in Afghanistan.

A black and white drawing of Reza Gul, an Afghan woman who had her nose cut off by her husband in 2016, hangs on the wall, next to a painting of a woman in a pink scarf who is being silenced by a hand covering her mouth.

According to Diba, she sold some of her artwork during an exhibition and job creation program sponsored by a Central Asian educational program but hasn’t sold any pieces individually, nor is she interested to do so.

However, she sold a second set of paintings at a recent exhibition held at Badakhshan’s Directorate of Information and Culture.

“My friend Amina Majidi, a painter, and I organized an exhibition/gallery. The directorate only allowed paintings of nature and flowers [to be showcased], no animated objects containing faces and living creatures, even birds, were allowed,” Diba says.

Diba made 8,000 Afghanis ($89.38) selling 4 paintings at the exhibition. However, “My main goal for organizing the exhibition was to give positive energy and hope to others.”

The event, according to Diba, paved the way for other events, such as book exhibitions to be held in Faizabad.

Since the Taliban’s return to power, the space for women has been shrinking. In a recent decree, the Taliban barred women from attending universities and refused to retreat from that position despite national and international outcry.

The time is just past 3 in the afternoon, before I leave for home Diba tells me the public’s opinion of painters remains negative.

“In addition to the lack of support and encouragement, the public’s view of painters is negative. Art is yet to have a place amongst women in our community,” Diba says.

Diba, who didn’t learn painting professionally, didn’t teach it until recently. She currently teaches painting to two teenage girls.

“I am going to teach painting due to high demand if the Islamic Emirate allows it,” she says. Although Diba likes theater and singing in addition to painting she is an introvert who wants to spend most of her time painting and being next to her tools.

“Nothing makes me sad when I am painting, even the mistakes or errors during painting are pleasant,” Diba says.

She adds, “When my father was alive, he was the first person to call me to congratulate me on my birthday. The best memories of my life are those with my father.”

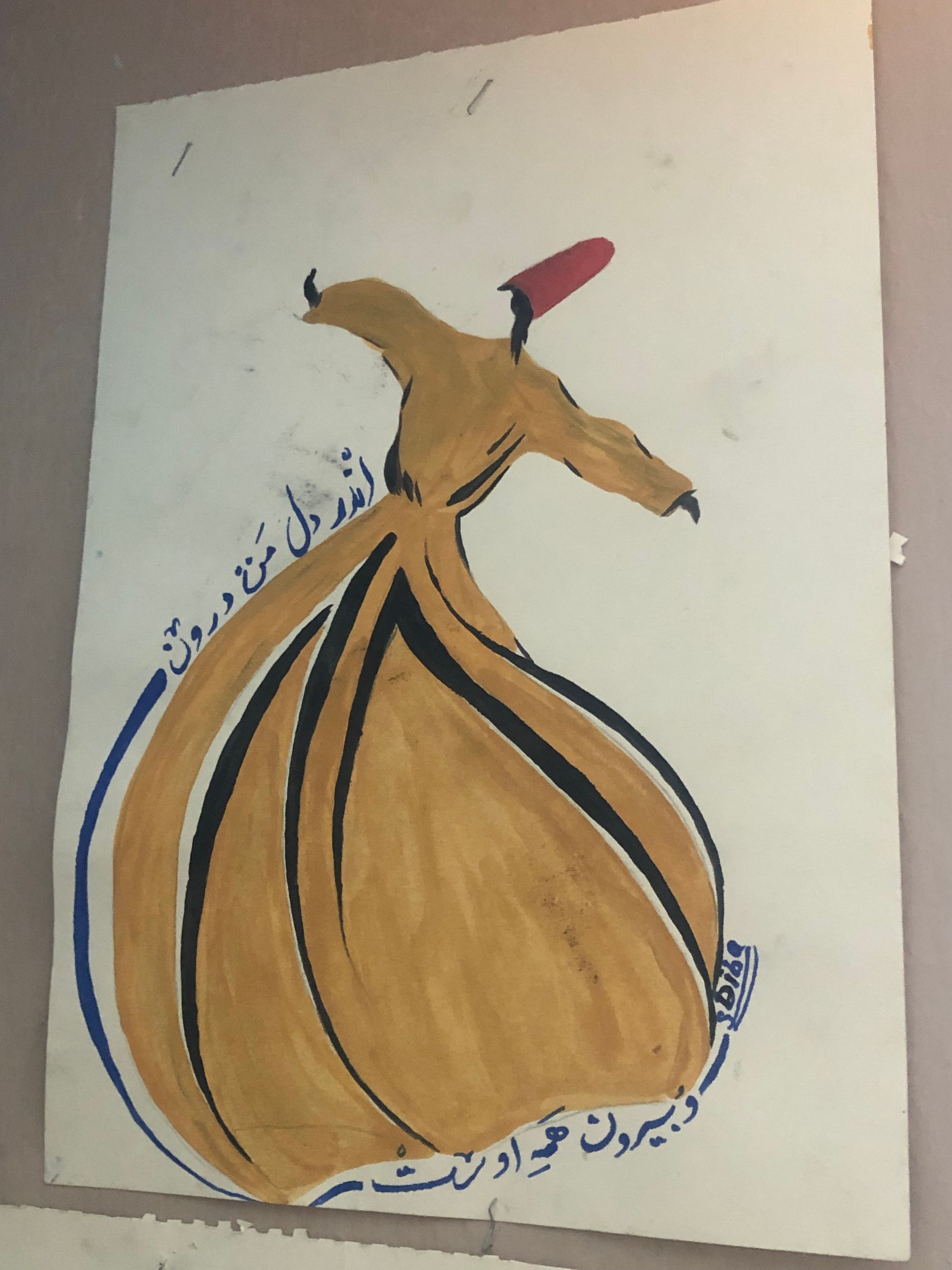

The most tragic event in Diba’s life was the death of her father. Diba fears that the responsibility to provide for her family will her from painting and drawing. Some of her paintings are a mix of painting and poetry together, which includes poems from Rumi and the whirling dervishes. One portrait is of Nasir- Khesraw Balkhi, an 11th-century poet from Balkh, a province in today’s northern Afghanistan.

“Rumi has his own unique personality and is completely different from other poets. I really like his poems about love. When you read poems by Nasir-e Khesraw or Rumi, you find out that Rumi’s poems are elegantly romantic while Nasir-e Khesraw’s are sharp/harsh,” Diba says.

Diba’s interest in reading is evident from the cabinet occupying one side of the room, stacked with books, family pictures, art, and tools. She reads novels, loves the world, and encourages the youth to read.

“The reason for staying in Afghanistan is the feeling of belonging to this room. What I want from life is this very room, the paintings, stand, brushes, and books within,” Diba says.

“My biggest hope is that my mother’s smile remains forever. My biggest concern is dying in a country without experiencing freedom.”

Alive-in is a not-for-profit media agency that mentors journalists from underrepresented communities to increase local and national understanding.

If you are able to support our work financially, please click the button below.