Discrimination Persists Despite Prevalence of Disabled Adults

Afghanistan has one of the highest rates of disability in the world. In addition to suffering from disability, Afghans with the condition have to also endure society’s lack of awareness and ridicule towards them.

— One Day in Afghanistan —

Written by Abdul Karim Azim, edited by Mohammad J. Alizada, & Brian J. Conley

Alive-in is a not-for-profit media agency that mentors journalists from underrepresented communities to increase local and international understanding. Subscribe to receive our stories directly in your inbox.

HERAT — Afghanistan has one of the highest rates of disability in the world. According to the Organization for World Peace, disabled Afghans are arguably the country’s most vulnerable cohort and, “[S]uffer from ongoing neglect, stigmatization and discrimination.”

A study by the Asia Foundation published in 2020 stated that 80% of Afghan adults live with some form of disability – 24.6% mild, 40.4% moderate and 13.9% severe. There is no information on or detail about the ratio of natural disability as opposed to disability caused by other factors including the continuous conflict in Afghanistan, but according to the study, for every individual killed in conflict, three others sustain life-altering injuries, often resulting in long-term disability.

The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) annual civilian casualty report of 2019 said 35,000 people were killed and 65,000 others were injured since the mission began systematic documentation of civilian casualties in Afghanistan in 2009.

In today’s episode of One Day in Afghanistan, Alive in Afghanistan’s Abdul Karim Azim profiles a day in the life of Somaya Tawanmand, a “little person” from Afghanistan’s western Herat province. “Dwarfism” is considered a disability in Afghanistan but Ms. Tawanmand has never thought of herself incapable of doing anything and says those otherwise abled can be productive members of society like every other able-bodied person.

I start my 10-kilometer journey based on a scheduled meeting with Ms. Tawanmand on an early Sunday morning and head towards the Peer-e Herat Charity Foundation and Disability Rehabilitation Center, Somaya’s workplace.

It’s now 08:30 am as I reach the gate of the foundation. After registering myself I enter the institution and wait for Ms. Somaya. 15 minutes later, a yellow rickshaw with a black top and pink doors pulls up to the gate and Somaya hops off. We greet each other and enter her workplace while talking.

Somaya is 23 years-old, a resident of Herat city’s 8th district and lives with her 13 member family, including her parents, six sisters and four brothers. She has a bachelor’s degree in Dari Literature and heads the handicraft department of the foundation that she joined some five years ago.

Her routine is to get up early in the morning, pray, and read the Quran–which takes about 30 minutes of her time every morning–then eat breakfast and prepare for work. The yellow rickshaw that brought her today is contracted to transport her to and from work for 1,500 Afghanis ($16) a month. She usually gets to work at 8:30 each morning at the foundation where she teaches handicrafts to 10 students.

We enter Somaya’s classroom where she distributes a pen and a notebook to every student in her class. While the class practices drawing, she helps by showing the students how to draw. I really like the way she speaks to her students; she uses kind and sweet words to address them. One of the interesting things I notice is there is a disabled person using his mouth to draw while Somaya observes and comments on how to draw the lines better.

Ms. Tawanmand finishes her class around 9:30 as I ask her about her work and challenges. She sighs and laments people’s behavior towards those otherwise abled.

“I am insulted and made fun of at least five times from the time I leave home to the time I get to work every day,” Somaya tells Alive in Afghanistan.

“They call me names like shortie, paralyzed, poor, and disabled in insulting tones. I was once slapped by a man and still feel the pain,” Somaya says, talking about the time she was made fun of by a man, only to be slapped for lashing out at him.

Her demand of all families is to inform their children not to bother people with disabilities. Somaya is still single and has so far not decided to marry. Her family is not pressuring her to get married because they worry that her future husband’s family will not respect her because of her dwarfism.

According to Somaya, the handicrafts she and her students made used to pay for her university and transportation fees, but her sales have significantly dropped since Afghanistan’s western-backed government collapsed in August of last year. Afghanistan’s assets were frozen and aid was largely halted following the Taliban takeover, sinking the country deeper into a growing economic and humanitarian crises.

“For now my family pays for my transportation fees although we are not doing well economically,” Somaya says. The foundation has told her that they will help her find work so she can take care of her own expenses, but it hasn’t happened so far. Ms. Tawanmand works at the institution on a voluntary basis. The products she and her students make include kitchen decor, coat hangers, fruit baskets, tissue boxes, candy servers, and artificial flowers for women.

It is now 10:30 am, time for Somaya to go to her English class. She leaves her classroom with enthusiasm and eagerness. The English class is taught by Freshta Bahador, another volunteer who started working at the foundation a couple of months ago. In total there are 15 students who learn English here.

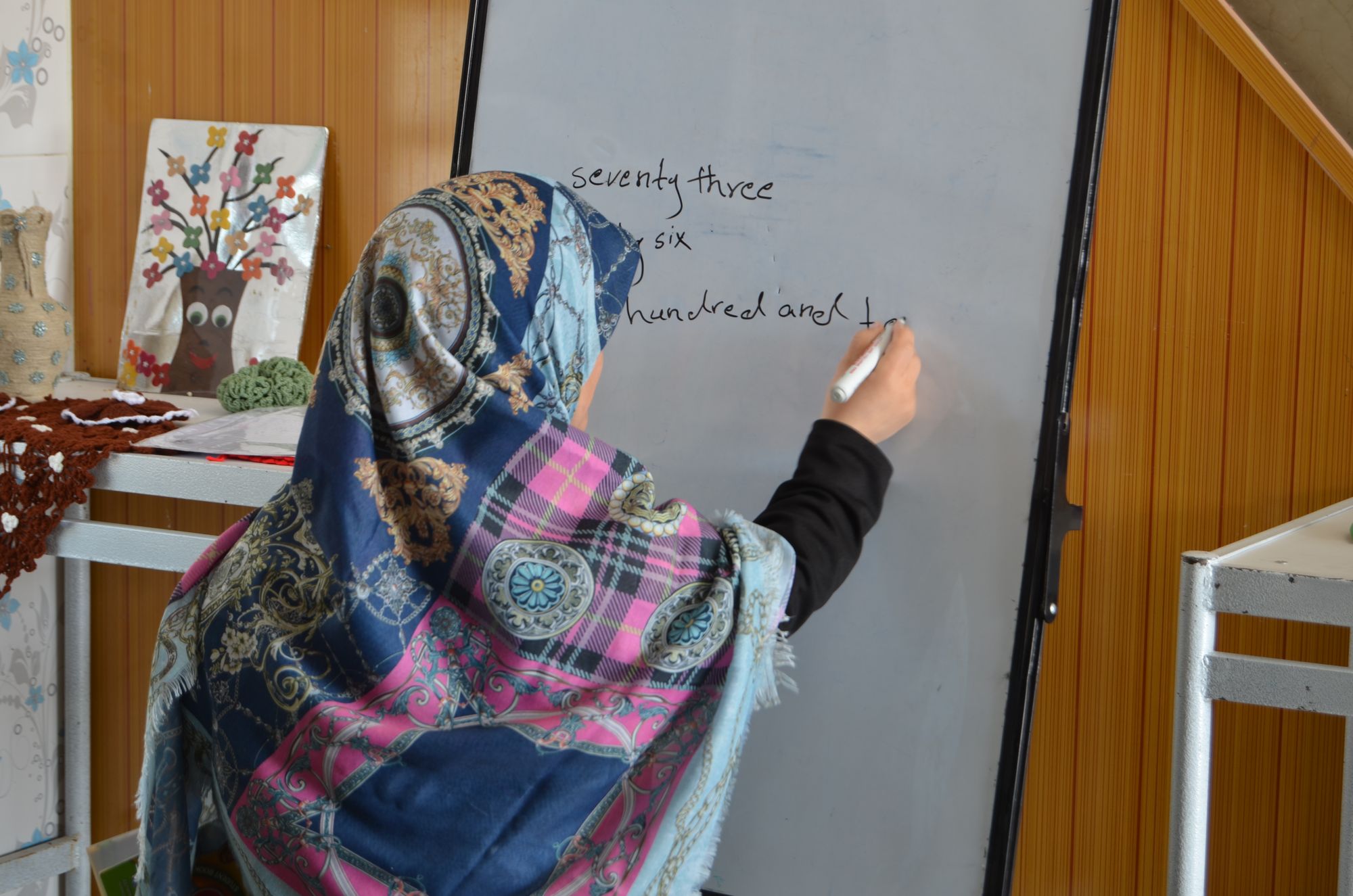

Freshta arrives and starts the lesson. I sit and watch from a corner, while filming at the same time. Ms. Bahador starts by asking the students to repeat their previous lesson. Somaya raises her hand, goes in front of the class and starts by explaining the lesson they learned by writing it on the whiteboard in the front of the class.

“Seventy Three, ninety six, one hundred and ten, two hundred and sixty one,” Somaya writes on the board after thinking about each number they have learned.

After finishing writing on the board, Ms. Bahador asks Somaya, still standing in front of the class, about shapes.

“Is it a square?” Ms. Bahador asks about the shape of the book she is holding, “Let’s Go”, a beginner English book.

“No,” the class says in unison.

“It is a…. rec,” Somaya tries to think of the shape, “A rectangle”.

Ms. Bahador nods her head in agreement.

The class of 15 students repeats every word Freshta utters with enthusiasm. Ms. Bahador is very kind and teaches her students with a positive attitude. The class is over at 11:30 sharp after which I take the opportunity to speak to Freshta.

“Somaya is one of the most talented students in my class. Although she started the class late, about a month and a half into the grade, she caught up quickly,” Ms. Bahador says about Somaya.

At 12 pm, everyone gathers and heads to the dining hall. I exit the foundation to have lunch outside, pray, then come back. I return to the institution around 1:30 pm and meet Abdul Ali Naawdost, the head of the foundation. He is busy going from one room to the other for inspection using his electric wheelchair.

“The Peer-e Herat Foundation was established in 2003, all of the organization’s expenses are paid by well-off local Afghans,” Mr. Naawdost tells Alive in Afghanistan.

According to Abdul Ali, the center houses 65 of the most vulnerable disabled Afghans. Services at the foundation include technical and vocational training, literacy courses, calligraphy, crafts, English, and painting classes among others.

Abdul Ali talks about Somaya’s reclusivity and creativity. “Somaya used to be super reclusive and isolated, she had her reasons, social disrespect and insults hurled at her from the public chief among them. She refused to get out of her house and hated herself,” Abdul Ali says.

A disability identification team working with the foundation registered her, spoke to her family and brought her to the foundation, after which she became a member.

“She started feeling better and felt that she is a member of the society,” Mr. Naawdost says, adding that Somaya has changed a lot and is much better now, “compared to 2 or 3 years ago.”

Mr. Barakzai wants the international community and aid agencies to pay special attention to the disabled community in Afghanistan, who suffered from the past two decades of conflict that Western countries were involved in since the US-led intervention overthrew the Taliban in late 2001.

It’s now 2:30 pm, I thank Mr. Naawdost and go to Ms. Tawanmand once again who reitirates Abdul Ali’s points before Somaya heads home.

Somaya wants families to improve their culture of name calling, insulting and disrespecting those otherwise abled, stop calling them blind, lame, paralyzed, and short and instead, understand disability.

If you are able to support our work financially, please click the button below.