Dialysis Clinic Like a Family

Alive in Sudan speaks with a nurse, who is also a patient, about the challenges facing dialysis clinics during the current war.

reporting by Mayada Abdullah

written by Logain Ali, with support from the Alive-in/ Editorial Team

This story is part of a partnership between Alive-in/ and DT-Institute to support Sudanese journalists inside and outside Sudan. DT Institute is both a funder and an implementer of peace and development projects. More stories can be read in Arabic on the Alive-in/Sudan Facebook page.

Alive-in is a not-for-profit media agency that mentors journalists from underrepresented communities to increase local and national understanding.

If you are able to support our work financially, please click the button below.

NURI, NORTHERN STATE–Since the start of the war in April 2023 in Khartoum, an already underfunded healthcare system has been pushed to its breaking point. Although many healthcare facilities in other parts of the country have witnessed a brief revival; artillery attacks, power outages and the overwhelming surge in demand have crippled many facilities.

As the war continues to spread coupled with extreme climate conditions, healthcare workers struggle to keep up, while patients face increasing obstacles in accessing consistent care.

Alive in Sudan met with Adeela Omer Rizq moments after her routine treatment in Nouri, Northern State. Adeela is a 32 year old mother, nurse trainee and a patient at Nuri Dialysis Center, where she receives regular kidney dialysis treatment and has been doing so since 2017.

Adeela radiates positivity, is a community pollinator and carries her sense of responsibility with pride. Although she had just finished an arduous session, she was focused on ensuring that patients coming in after her had their food and refreshments ready. Under the shade of a tree, she ordered a cup of tea for us to enjoy as she prepared for the interview.

Adeela laughed as people approached her for one thing or the other, “I have an interview to conduct, I am working.”

“Dialysis needs a break, and I have no way to rest because life is extremely overwhelming. The kids and the necessities leave no room for rest. Ideally, someone undergoing dialysis should have a room with an air conditioner so they can lie down, not get thirsty, and not get tired. Even water makes you feel sluggish when you drink it, but in these five years, I haven’t had time to rest.”

Adeela’s health challenges began five years ago, “At first, I had sores, and they kept telling me it was just an infection. Every time I got tested, it would come back as malaria or typhoid. Then suddenly, I was in the advanced stage of kidney failure and had to start dialysis immediately.”

Born in Northern State, Adeela moved to Khartoum for her high school education and after graduating, she married and moved to Nile River State, where she lived with her husband with their four children - three sons and a daughter. Her life took an unexpected turn when she began experiencing mysterious symptoms.

“I was a housewife living with my husband in Nile River State,” she explains, “but when my illness worsened, we had to separate. My husband stayed with our sons, and I moved back to Northern State with my daughter to be with my family.”

Having to undergo treatment, she moved back to her hometown in Nouri, where her family’s support became essential to her coping and recovery. “My father was the one who encouraged me and helped me accept the idea of dialysis. He’s the one who continues to motivate me in life. To this day, he and my siblings support me, and I live with them while they take care of my responsibilities.”

Despite receiving a delayed diagnosis, Adeela faced her situation with strength, “I wasn't accepting of dialysis at first,” she admits. “I had this idea that dialysis was a death sentence. I thought once you start dialysis, you won't live long, but after some convincing and getting through my first session, I adjusted. Now dialysis feels like a normal part of life for me. If I miss a session, I feel restless and anxious. It has become part of my routine.”

Adeela typically spends four hours on the dialysis machine per session, though sometimes her sessions are shorter, she also shares some insight regarding the monitoring of her condition, “You start your day normally, then you sit on the machine for four hours if everything is fine—no fever or malaria or anything like that,” she explains.

“You eat, chat, and finish feeling okay. But if your blood pressure is too high or low, or if you haven’t eaten during dialysis, you run into problems. So, you have to take precautions—don’t go in hungry, keep your blood pressure stable, and adjust your diet accordingly.”

According to E. Konozy in a paper released in March of 2024, the targeting of medical professionals in Sudan forced them to make decisions that left many patients without the essential care needed. A joint report released by the American Society of Nephrology, European Renal Association and the International society of Nephrology expressed deep concerns for kidney patients struggling under the dire conditions in Sudan.

Approximately 8,000 people in Sudan rely on hemodialysis for survival, however the supply chain for essential hemodialysis materials is severely disrupted, making it difficult to obtain and deliver these vital resources, particularly in areas heavily impacted by conflict. Although Nuri Dialysis Center is far away from conflict, during the first month of the war many facilities in the Northern State refused to receive patients who are children, as they lacked professional personnel.

Adeela’s resilience is further bolstered by her desire to help others in her situation. After beginning dialysis, she pursued training in nursing and pharmacy. “I felt the need to help others like me, especially the elderly patients who often asked me for help,” she says. “When you’re on the machine, you can’t refuse someone’s request, so that’s why I decided to study nursing. Not for money, but to be able to help them.”

She successfully completed her training at the Military Hospital in Nuri and now works with the Meroe Renaissance and Hope Makers Organization, a charity providing medical treatment and supplies to the dialysis center and other facilities for chronically ill patients. Adeela is responsible for tracking medications for kidney patients and reporting any shortages.

“I wanted to help because many of the patients are older than me and in need of support,” she says. “Sometimes, they would ask me for things while I was on the machine, and I couldn’t refuse them. So, I thought, why not study nursing so I can help them better? Now, I can respond to their needs immediately.”

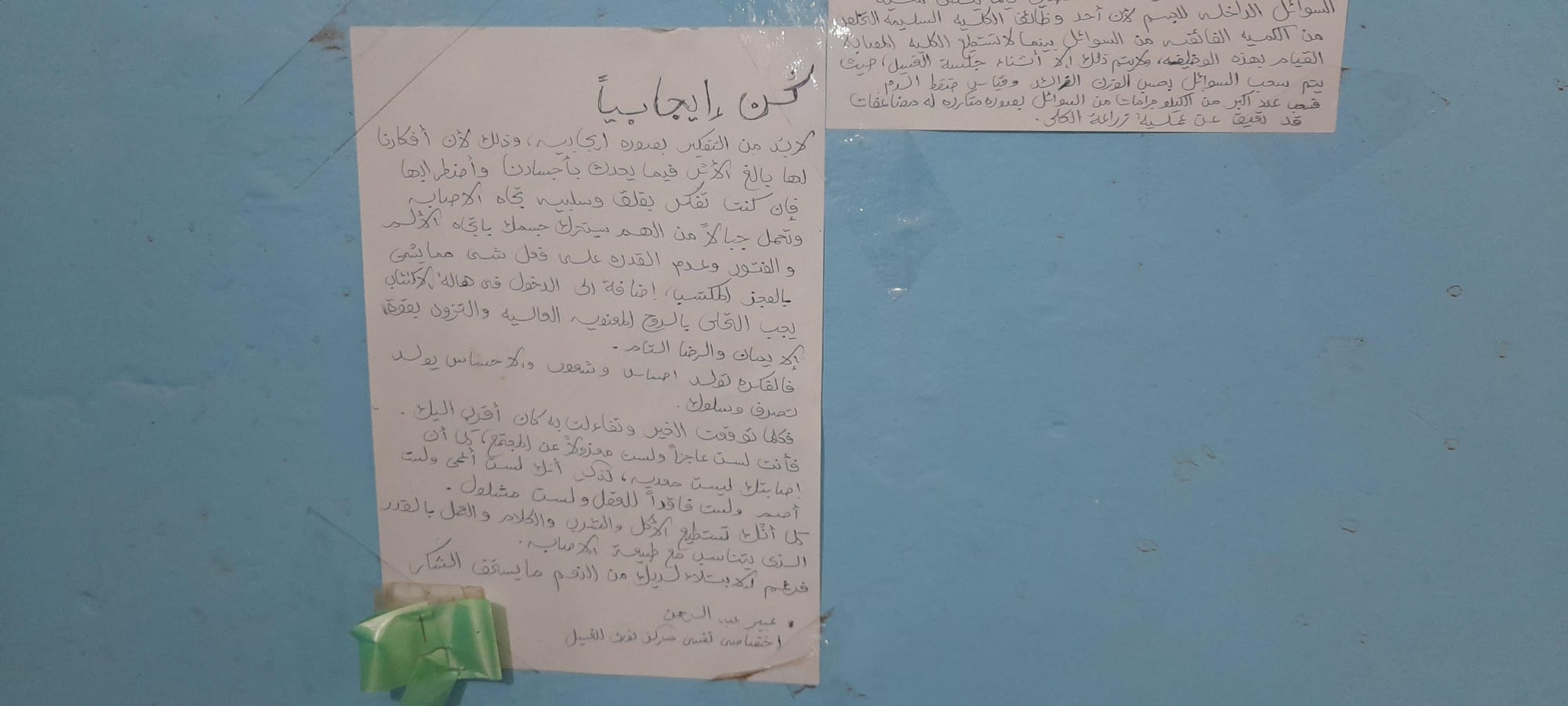

Dr. Abeer Abdelrahman, a specialist in Health Psychology at the dialysis center, emphasizes the psychological toll of chronic illness in Sudan. “Many may accept their illness and be in relatively good health, but societal misconceptions affect their mental state, leaving them feeling that dialysis has halted their lives and crushed their hopes. Society reinforces these thoughts.”

The doctor notes that Adeela’s story is one of exceptional resilience, largely due to her family’s unwavering support: “Her father stood by her in a way that truly helped her move forward. He lifted her from a very dire situation and has been with her throughout her treatment journey, as have her siblings and family. They have stood by her without making her feel deprived or in need of anything.”

However, Dr. Abeer also highlights the added strain the war has placed on patients. “Since the war began, the number of patients has surged, and many of them are dealing with severe psychological trauma due to displacement and loss of livelihood. The financial strain on patients has increased because this illness requires consistent medication, regular dialysis, and frequent specialist visits. The disruptions to daily life caused by the war have pushed many into depression, anxiety, and difficulty adapting to their new reality.”

Despite these challenges, Adeela remains optimistic. “The hope I hold is from God,” she says. “There are many kind people who give you hope, and you must have faith that God will bring healing.”

When Alive-in Sudan asked if she would continue as a nurse trainee if she were to receive a kidney transplant, Adeela stood by her unwavering commitment to helping other patients, regardless of her health status.

“My acceptance of dialysis and this illness is all thanks to my family and the team at the center,” Adeela concludes. “We are like one family here—we eat together, joke together, and there’s no distinction between doctors, managers, and patients. If they offered me treatment in another center, I wouldn’t leave. The community here at the Nuri Dialysis Center is what gives me the strength to continue.”