An Education, If You Can Afford It

Special needs children are the most vulnerable and neglected group in Afghanistan. Essential facilities, particularly access to education, are severely lacking, adding to their struggle.

Written by Samira Wafa

ZARANJ, NIMROZ — Special needs children in Afghanistan are among the most vulnerable groups of children. They are deprived of their basic human right to essential facilities, particularly access to education. Over the last several decades, as governments and wars have come and gone, disabled children continue to be barred from attending public schools.

In this article, Samira Wafa speaks to three students and two teachers at Imam Bukhari, a private school in Zaranj City, the capital of southwestern Afghanistan’s Nimroz province. The students interviewed are all special needs children enrolled at Imam Bukhari Private School because their families believed their needs were not being met at public schools in their communities.

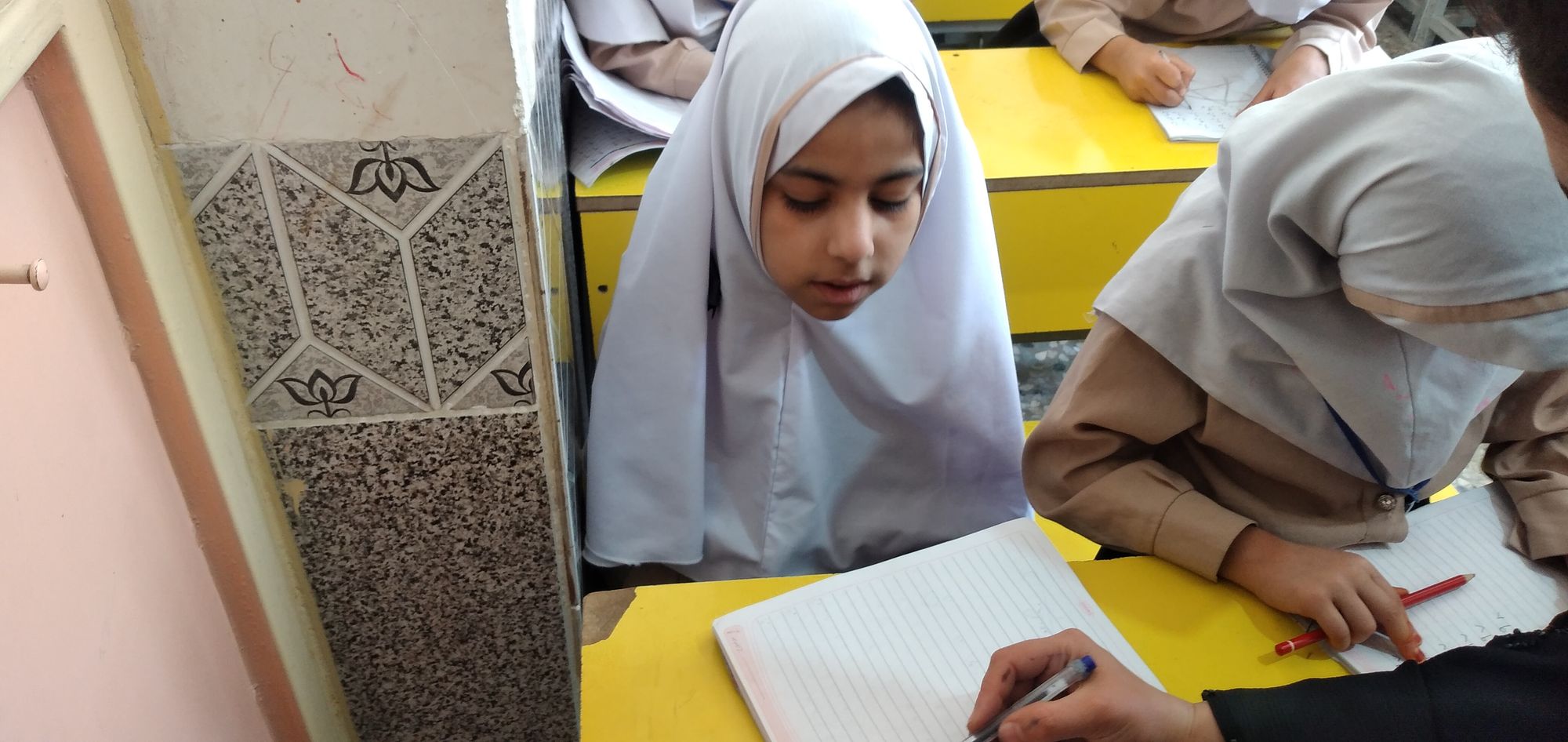

Atifa Karimi, the headmaster of Imam Bukhari, gathers the students every morning at 7 am. However, 11-year-old Niyayesh, due to her physical disability, joins the lineup a little late. Her father transports her to school each day. When they arrive he takes the stroller Niyayesh uses as a wheelchair from the back of his car, and assists her in entering the classroom.

The students form orderly lines across the schoolyard, with boys mostly dressed in dark blue shalwar kameez and girls wearing beige tops and matching pants, along with a dark blue skirt and white scarves. They place their hands on their chests as the Afghan national anthem plays. Niyayesh sits calmly in her stroller while a girl nearby smiles at her.

The students file out of the lines after the national anthem and head to their classes. Niyayesh’s father takes her from the stroller and carries her to her classroom, sitting her down on her designated chair at the front of the class.

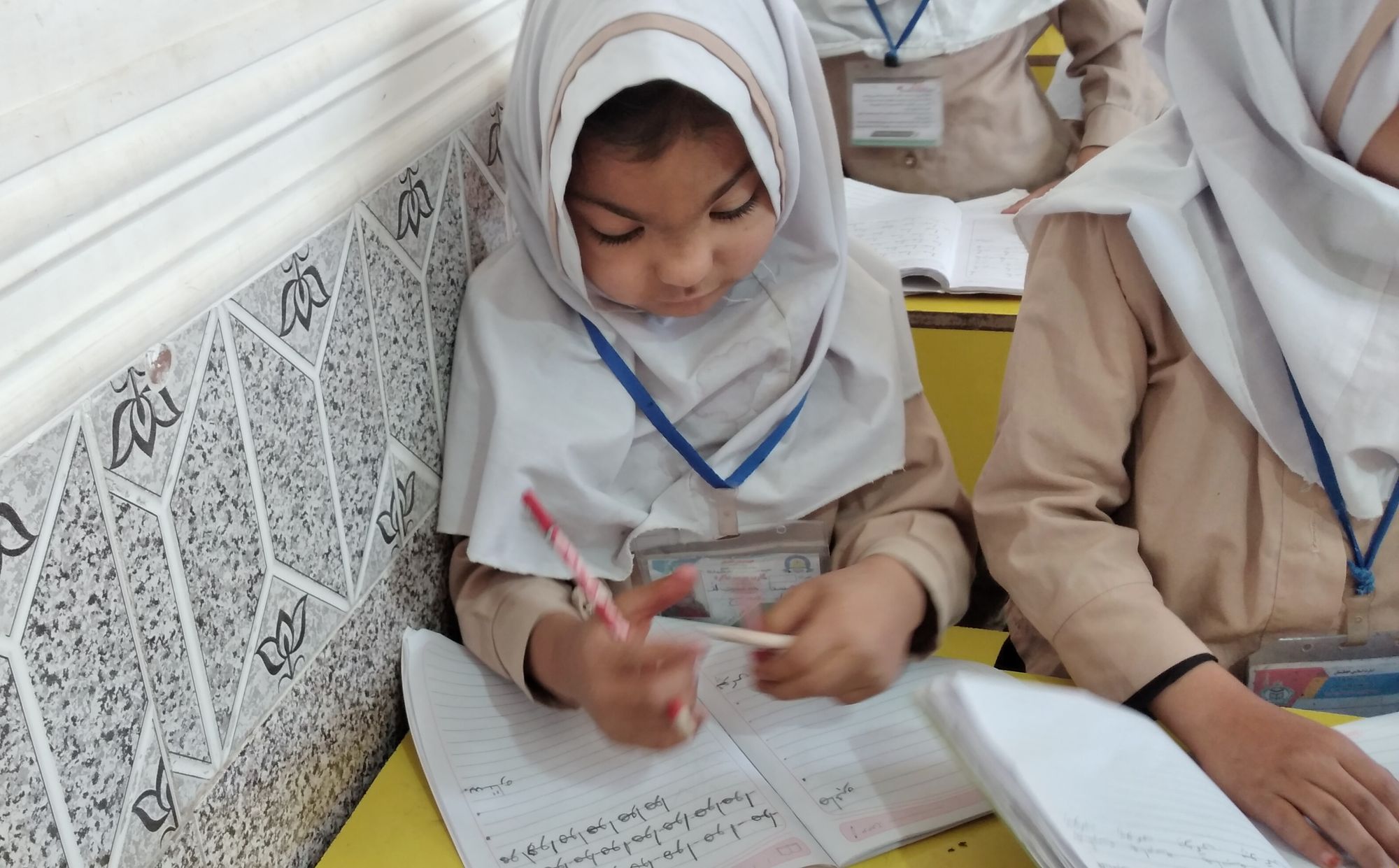

Niyayesh is not the only child at Imam Bukhari struggling with a disability. My attention is also drawn to Hania Baloch, a 10-year-old girl who has been placed in a class with 5 to 6-year-old children. She sits in the middle of the classroom and engages in self-talk. Hania has a mental disability and requires assistance from others to wipe the saliva running out of the corners of her mouth. Only the headmaster can comprehend her speech and understand her needs.

Mrs. Karimi adds that Hania used to bite other students and teachers after she was enrolled but is, “Currently the calmest student among her classmates.”

Mrs. Karimi reviews Hania's homework. Although she had assistance from her sister, Hania has managed to write only one page. Hania has limited ability to recognize shapes and she finds it challenging. Pointing to a circular shape in her notebook, she says, "I drew and colored it, but my sister Alina wrote the homework."

The triangle, circle, and square shapes on the single page are painted yellow and red. Smiley faces are drawn into the shapes. As she talks, Hania smiles at Mrs. Karimi who briefly holds her hand.

“Hania wrote this?” Mrs. Karimi asks, “Yes,” Hania answers–although her answer is unintelligible to me, Mrs. Karimi clearly understands her.

In addition to her mental disability, Hania struggles with a speech impediment. When the teacher asks her questions, she responds with only smiles and unintelligible mumbling. She primarily desires to play and has retained very little of the education she has received thus far, and is developmentally delayed by six years. Hania's bathing, hygiene, and other personal needs are attended to by her sister and mother.

“Families have a 50 percent role in educating their children, but Hania’s family never asks her about her studies. Sometimes her father calls and asks if she needs anything, but her mother never called to ask why Hania didn’t write, or why isn’t she saying anything. Hania would have had more progress if her parents took a more active role,” Mrs. Karimi says.

“These children have a right to study. Hania’s parents tried to register her at a government school two years ago, but despite education being free for Afghan children, the school and teachers did not accept her, leaving her to lag behind other children [of her age group],” Mrs. Karimi tells Alive in Afghanistan.

Mrs. Karimi further explains that Hania's intellectual level is comparable to that of a 4-year-old. According to Mrs. Karimi, Hania has had this condition since childhood. Initially, she struggled to adapt to her classmates and teachers, occasionally displaying aggressive behavior or becoming upset. However, with the dedicated support of the teachers in this school, she has gradually become more sociable and calm. Now she no longer disturbs her classmates and is able to study alongside them like any other child in the classroom.

Ms. Karimi, who is able to understand Hania's speech impediment, quotes Hania, saying, "Before, my mother used to bathe me, but yesterday I bathed myself. I like studying and coloring."

Next, I move on to the 1st grade, where there are two children living with disabilities. One of them is Niyayesh, who was born with congenital paralysis. Niyayesh is currently engaged in practice sessions with her teacher, Mrs. Karima Naderi. Niyayesh lost her mother in a traffic accident a year ago and is now being cared for by her father and older sister, Setara. Niyayesh missed years of school because public schools refused to admit her. As a result, she has fallen behind by four years.

“What did you do during the weekend?” Mrs. Naderi asks Niyayesh.

“I wrote,” she says calmly, looking at her teacher with full attention.

“Who helped you with your homework?” Mrs. Naderi asks.

“Nobody,” Niyayesh says.

“You wrote it all by yourself?” Mrs. Naderi asks.

“Hmmm [yes],” Niyayesh says, shaking her head in affirmation.

“Bravo, very nicely written!” Mrs. Naderi responds back, asking Niyayesh to read the first line of the last page, which Niyayesh has doodled a red flower and green leaves on the left side of the page.

One word after the other, as Mrs. Naderi points to every words by touching her index finger above the word, “Hashim, and Bahram, are blacksmiths,” pointing to the middle of the page as Niyayesh continues, “They make saws, and axes.”

“Good job you beautiful girl!” Mrs. Naderi responds.

“I am very happy to study. I want to become a teacher in the future. My family is very encouraging and supportive, especially my sister,” Niyayesh says.

Niyayesh is shy and doesn’t speak very much, but according to her teacher Mrs. Naderi, she is super interested in school.

Niyayesh says that although it’s difficult to attend school with her condition, she wants to learn. Her family’s encouragement has made her try harder.

While checking homework, Mrs. Naderi praises Niyayesh’s handwriting, saying, “Niyayesh has beautiful handwriting and fully observes writing principles. She has exceptional talent and will reach high places one day. She is one of our honor students who has demonstrated her abilities in the course of four months [since starting at the school.”

Mrs. Naderi continues the lesson by reciting a prayer first, then explains the Persian letter "ه" and its usage in sentences to the students. She writes words that contain the letter "ه" on the whiteboard, such as "Hawa -هوا" (air), "Hamsaya - همسایه" (neighbor), "Sitara - ستاره" (star), etc., and practices syllables and pronunciation with the students to help them grasp them.

While everyone else repeated after the teacher used their hands for movements, Niyayesh was only able to repeat, her hands unable to join in due to her paralysis. Mrs. Atefah, who has received training in physiotherapy, says Niyayesh, "Has osteoporosis, weak bones, requiring her to be under the sun for 2 hours every day. However, her mother did not pay attention to her need.”

Niyayesh says people look at her with disdain because of her disability when she attends parties or events.

After 45 minutes of teaching Dari and a short break, it’s time for math. After the break, Mrs. Naderi clears the whiteboard of the previous lesson and starts writing the numbers down while telling her students to write them down in their notebooks. The students follow by taking their notebooks and pencils out of their bags as instructed.

Niyayesh writes down the number 40 in her notebook while everyone else reads and writes 97 and 98. This is due to Niyaysh joining the school two months after the start of the academic year.

“I give Niyayesh separate attention after my session with other students and make her repeat and practice what she has learned,” Mrs. Naderi says.

The other student suffering from a disability in Niyayesh’s class is named Husna, she is seven years old. Husna’s head is larger than normal but her brain has not developed fully.

“I am two years old,” Husna responds after I ask her how old she is. Her teacher, Mrs. Naderi says Husna is slower in understanding the subject being taught, “She doesn’t know what a blacksmith is, how many letters [the names] ‘Hajar’ and ‘Sitara’ have, or who they are.”

Hajar and Sitara are Husna’s classmates, but Husna has difficulty recognizing or remembering people.

“Husna’s family told us they didn’t enroll her into public school due to the high volume of students and the lack of attention to their child. They feared other students would use derogatory and inappropriate terms toward Husna, further weakening her spirit. No inappropriate terms that would upset Husna have yet been said by anyone in this environment. She is a bit weaker and learns slower. She can vocalize very well, but struggles with identifying words,” Mrs. Naderi says.

Husna’s family is illiterate and cannot assist with her studies at home. The school is the only place where she can learn to read and write. That does not stop Husna or reduce her hopes for her future.

“I want to go to school, learn, play, have friends and companions, and become a teacher,” she says.

Mrs. Naderi adds that specialized schools for special needs children are necessary to prevent these children from lagging behind others. Naderi has not heard of any other media agencies doing reports about special needs children but hopes that this report serves as a wake-up call for Afghanistan’s current government and organizations serving children, such as the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).